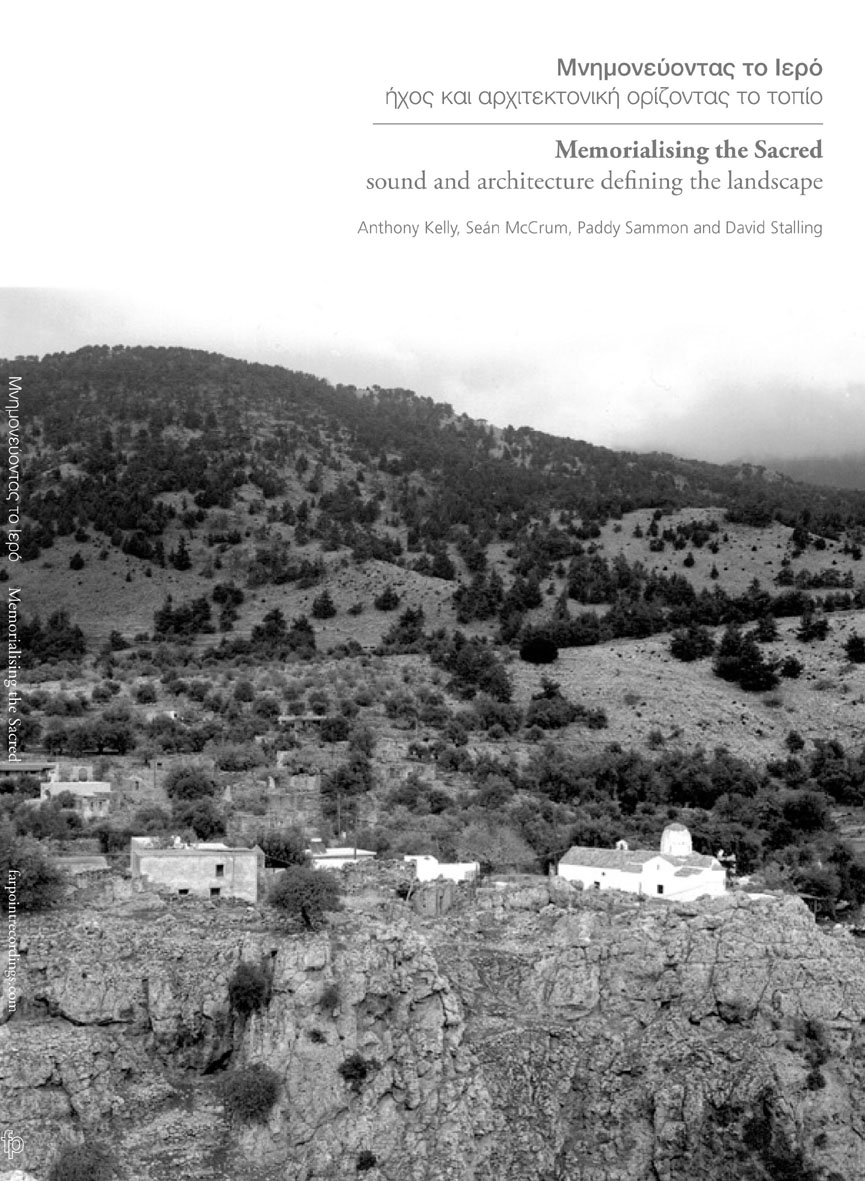

The following essay is by Anthony Kelly, Seán McCrum, Paddy Sammon and David Stalling, the curators of the Memorialising the Sacred exhibition running in the IAA Architecture Gallery from January to April 2018. It is from the publication Memorialsing the Sacred: sound and landscape defining the architecture (Paddy Sammon ed., Farpoint Recordings, 2018) and is reproduced here by kind permission of the authors.

The publication is available for purchase in the IAA Reading Room (€10)

One evening, during sunset, we went for a walk along the road from Anópoli to Limniá. There is a junction after about 20 minutes, where a side-road turns right, and a wayside shrine at the corner. About 300 metres from the junction, we saw a car turn into the side road and stop for a minute, then drive on. We were curious and continued walking. The driver had lit the lamp in the shrine. Its lightmade the shrine a marker of the junction at night. The shrine was important for this individual, defining this junction not just for the driver, but for whoever came past. To an outsider these shrines and churches may seem to be situated in the countryside for no identifiable reason. However, no building exists for no reason. Why is a church or shrine here? Why not somewhere else?

Visiting Loutró and Anópoli, we went hill-walking and kept coming across small churches and wayside shrines. We began to ask why these structures are at particular places. Their number and positioning made Loutró and Anópoli particularly rich resources for answering our question. There are two types of church. One at the centre of a village. The other an “outside church”, placed at the edge of a village, in the countryside or on the seashore. The second type may define the boundaries of a village or the point where two villages’ lands meet. They may also act as visual pointers, related to pathways in use before roads were built. A church made clear that a village was nearby and also defined its presence. A church on the shoreline or hilltop can act as a marker. It could be built to repay a vow. Others are positioned close to late-Roman or Byzantine ruins. In some cases they incorporate a basilica, or may be close to a Roman tomb. They may not project precise knowledge about these buildings, but a sense of the importance carried by a ruin and its role as part of a Christian structure. Wayside shrines frequently incorporate some or all of these elements. They were also often built to repay a vow, to show a place where danger was avoided, or where something bad happened. The shrine defines how individuals and their community see their relationship to a particular place, such as the junctions of paths and roads, which are unlucky places.

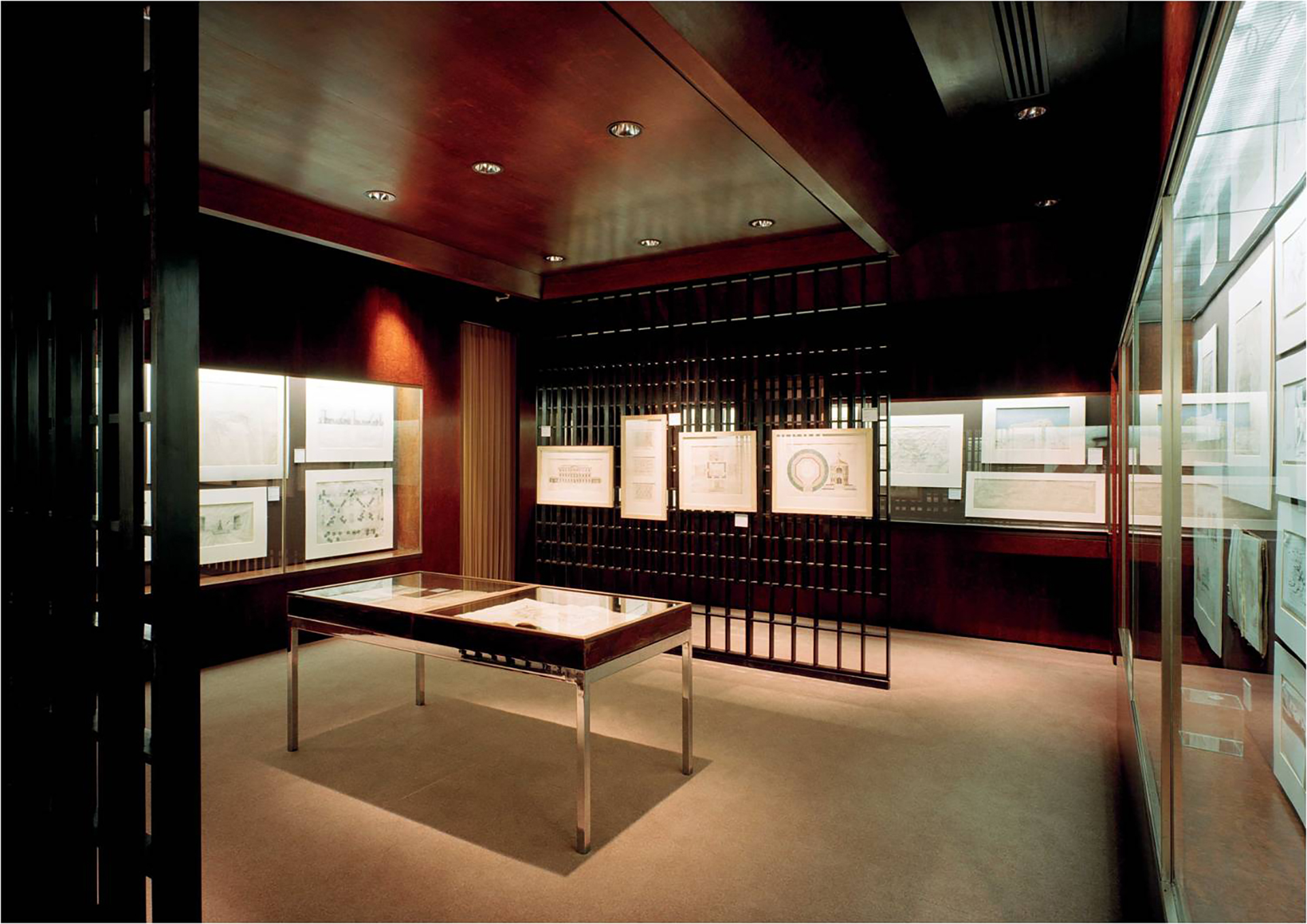

Although we have visited Loutró and Anópoli several times, we are outside observers of country churches and shrines and their role in their locations. We agreed to make a creative project from our perspective, different from that of local people. It involved transmuting our experience in those places to a different place, the Gallery of the Irish Architectural Archive, with its own strong persona, which determined our thinking on presenting the experience of these villages.

We needed the visual as well as sound, since both were parts of our experience of the places, and worked with black-and-white medium-format film, to state the visual presence of country churches and shrines. Such images make it clear that these are photographic, two-dimensional records of experience. Colour is now too close to replicating and, by implication, imitating a place. Recordings were made in and around where photographs were taken, then used to make a sound composition. Some small objects were also incorporated. The three dimensions and architectural presence of the gallery incorporate the two dimensions of photographs presenting objects; sounds add an additional dimension; the objects respond to the physical three dimensions of the gallery.

These churches and shrines have a complex role in defining where they have been placed. They are at the centre of how people define themselves and where they live. It is important not to perceive them as disparate objects, but as part of a network of how people relate their presence to their place. For us, they also provide a different point of definition in our experience of Loutró and Anópoli.

Anthony Kelly

Seán McCrum

Paddy Sammon

David Stalling