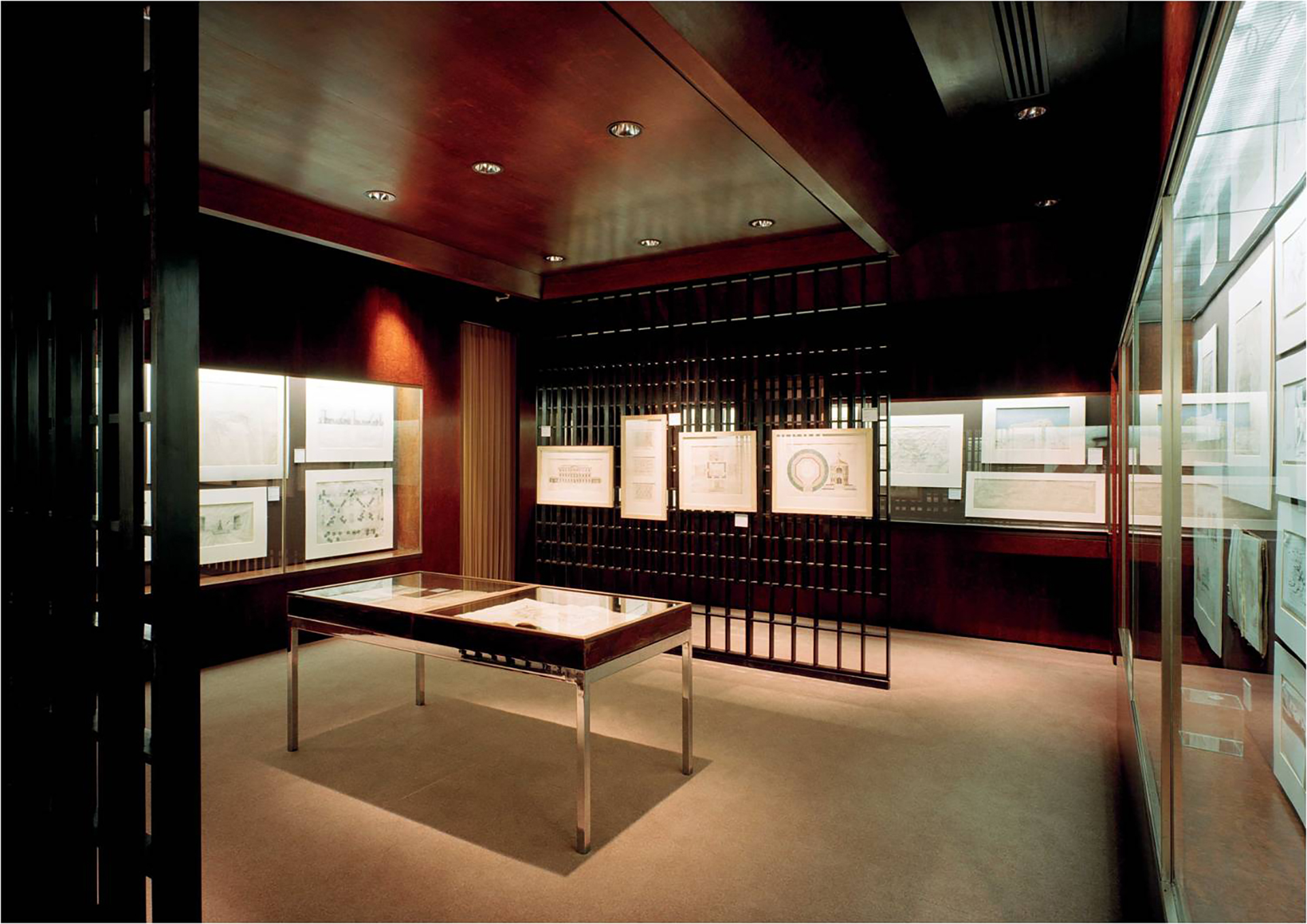

An introduction by Alistair Rowan given at the opening of the Pugin Revisited exhibition at the Irish Architectural Archive on Tuesday 24 April 2018

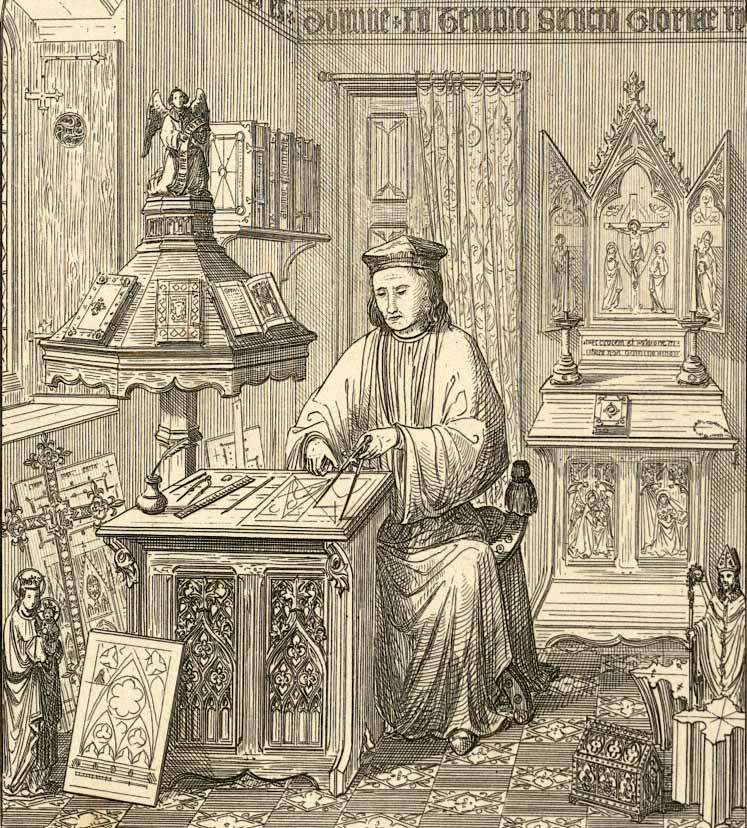

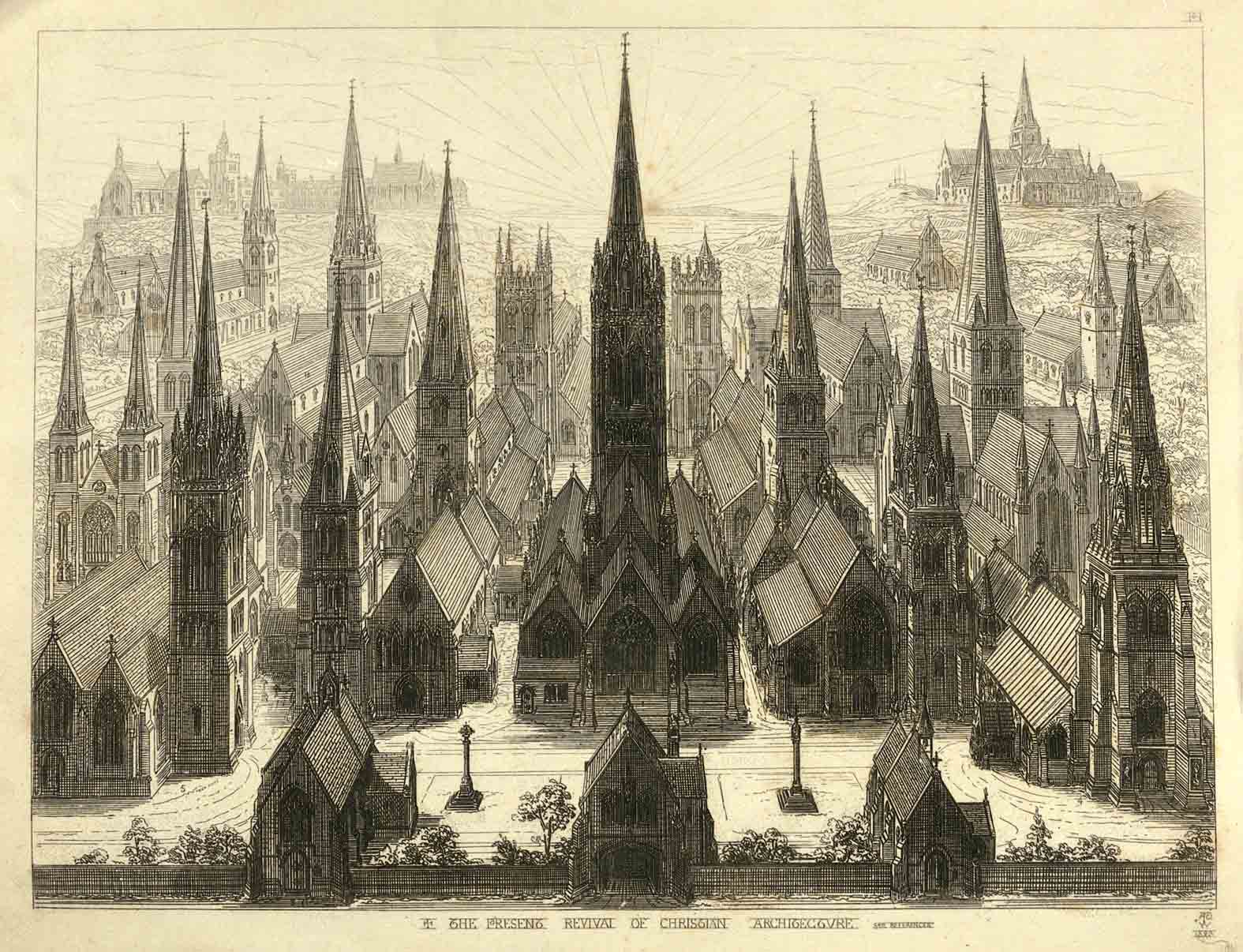

This exhibition consists of thirty-one drawings, shown either singly or in pairs within the one frame. There are also copies of two of the books published by Pugin, firstly The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture of 1841, with a highly romanticised picture of a medieval architect at work within his study, where a Gothic house-altar stands behind him, and chunks of tracery and ecclesiastical bric-a-brac lie cluttered at his feet. The second book, of 1843, is open at the celebrated frontispiece of fifteen of the architect’s own most creative designs for churches.

Pugin was always a polemicist. Think of the absolute irony implicit in that second title, thought up by a young man of thirty-one: An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture. Why on earth should an architect in early Victorian Britain feel the need to apologise for encouraging the revival of Gothic architecture, particularly when the scales are weighted in its favour by singling Gothic out as the only logical style for people of any religious faith and by calling it Christian.

Pugin was also a brilliant self-publicist who never minced his words. The new Classical churches built throughout Ireland, after Catholic Emancipation and before the Famine, were castigated by him as pagan, and he described buildings like Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral, Longford Cathedral, and St Mary’s Dominican Church, Cork, as simply ‘the vilest trash’. That did not make him popular with the clergy in Ireland but it gave grist to his architectural campaigns. ‘My writings much more than what I have been able to do have revolutionised the taste of England’ he wrote to his friend and business associate John Hardman in Birmingham in 1851, just one year before his death at the age of forty. In 1851 the Medieval Court at the Great Exhibition in London, bursting with examples of his designs, had been a runaway success and it was Pugin’s meticulous Late Gothic details that were even then clothing the entire fabric of the new Houses of Parliament at Westminster.

How did he achieve such dominance? This exhibition of a small but choice selection of the architect’s sketches prompts at least two answers: firstly there is the indomitable energy at the root of Pugin’s character which led him to make drawing after drawing of medieval architecture wherever he went and secondly there is his capacity for looking analytically at whatever he chooses to study.

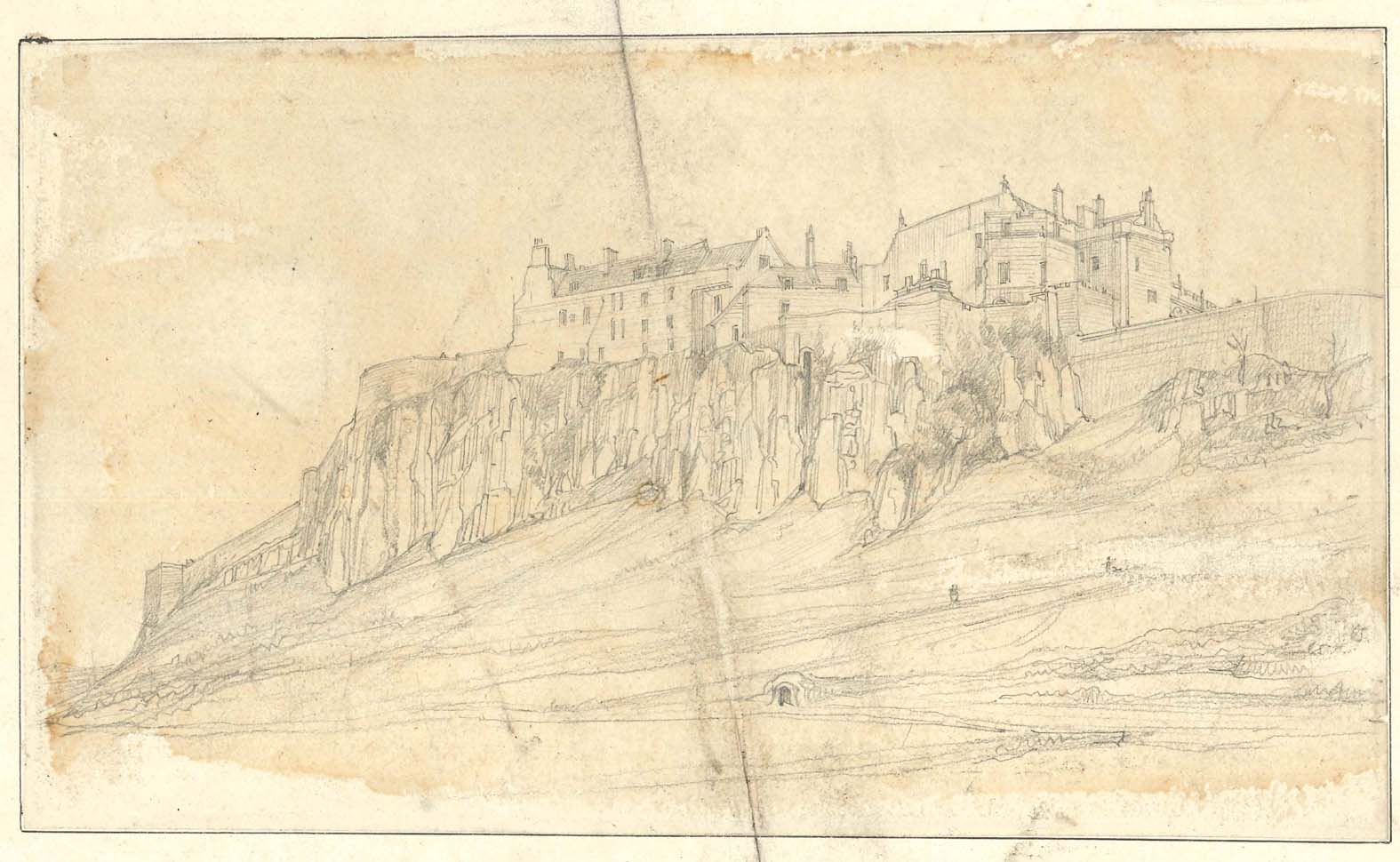

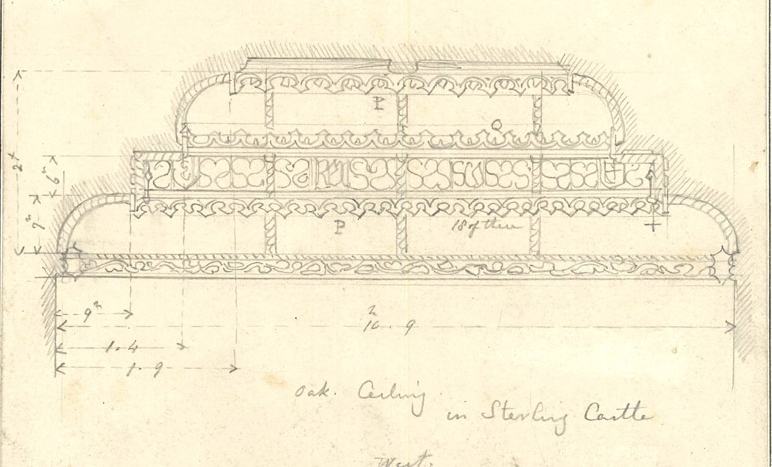

We may note these characteristics at least twice in the exhibition: first when Pugin visited the royal castle of Stirling in Scotland – a building which he records first in two neat topographical views, drawn in pencil, showing the bulk of the castle rising above the volcanic outcrop of rock on which it stands and, in a second view of the approach to the apartments of King James V. These drawings give a sense of the whole building but Pugin also took time to analyse a rectangular oak ceiling in detail, making a plan and sectional elevation of its design and expanding his understanding of the construction by very precise and accurate drawings of the carved decoration and lettering set into the ceiling.

I have the feeling that he must have got someone to lend him a ladder since he notes precise measurements taken from the high cove of the ceiling at the top of the room and he could not have drawn the details of the carving without close access. Now this is the important point. The detailed knowledge that Pugin acquired of actual examples of Scottish medieval joinery in this way would immediately inform the decoration of two Gothic libraries at Duns Castle in Berwickshire and Taymouth Castle in Perthshire for both of which he supplied designs. The effect of these rooms was rich, new and stunningly authentic. No wonder Puginian Gothic met with approval and encouragement.

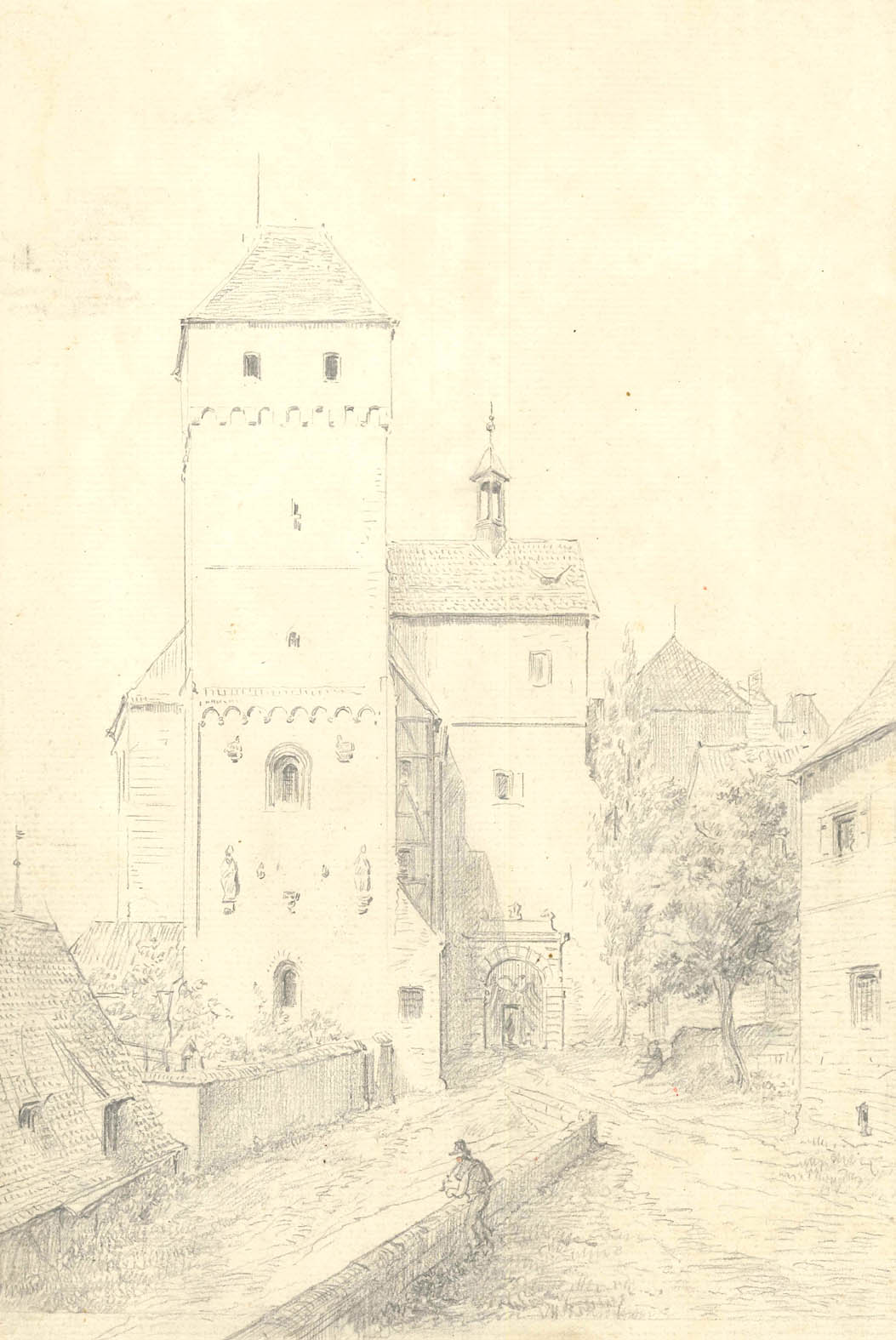

Nuremberg is the second site widely recorded in drawings now held in the Irish Architectural Archive. Pugin visited the city in the summer of 1838. It is a wonderful medieval town, which must have delighted him. At that time the circuit of the defensive walls was marked by no less that eighty-eight interval towers of which, even after the Second World War, fifty-seven remain. There are handsome pictures in the exhibition of two of the interval towers one of which, up beside the castle, has a Romanesque chapel incorporated at its base.

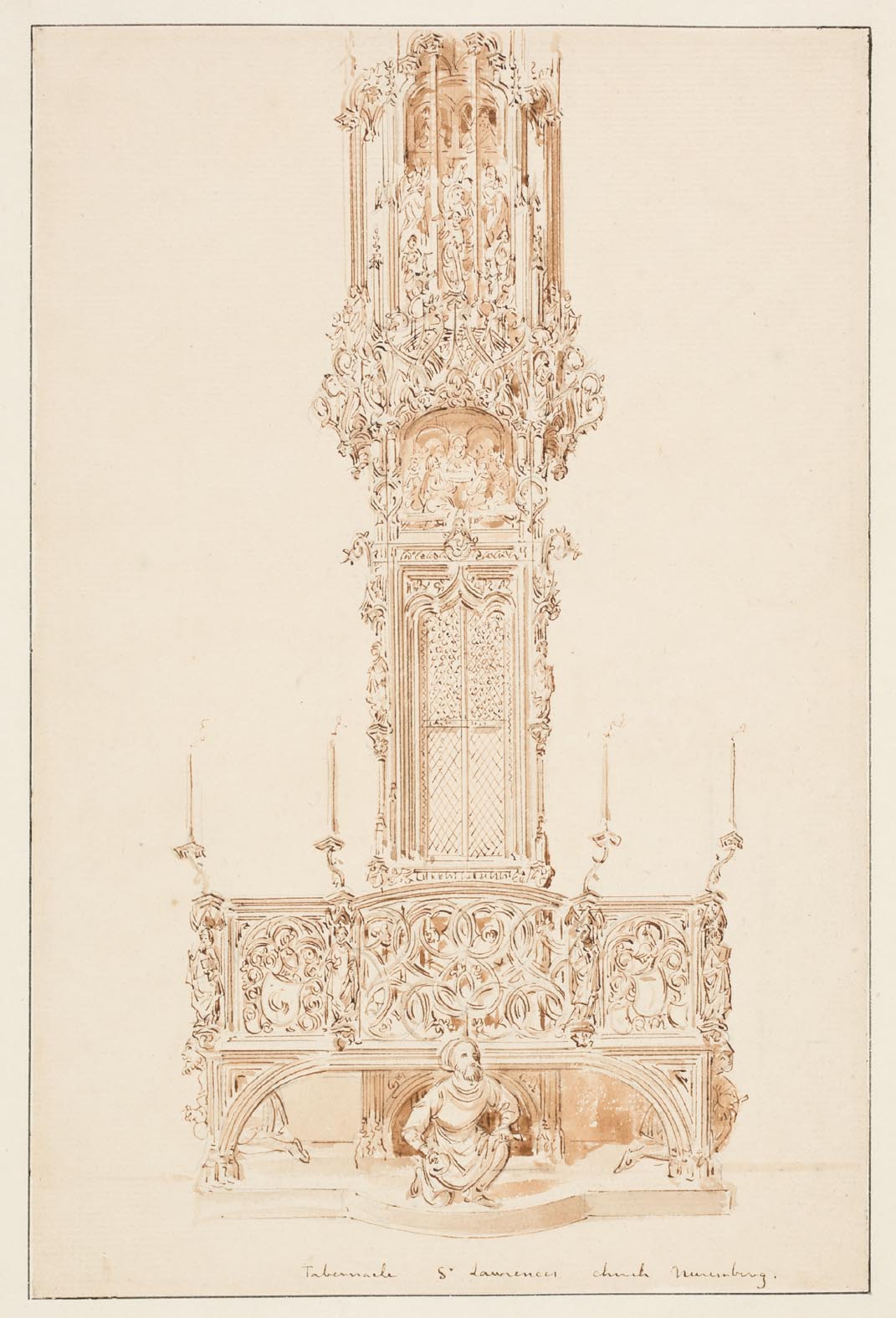

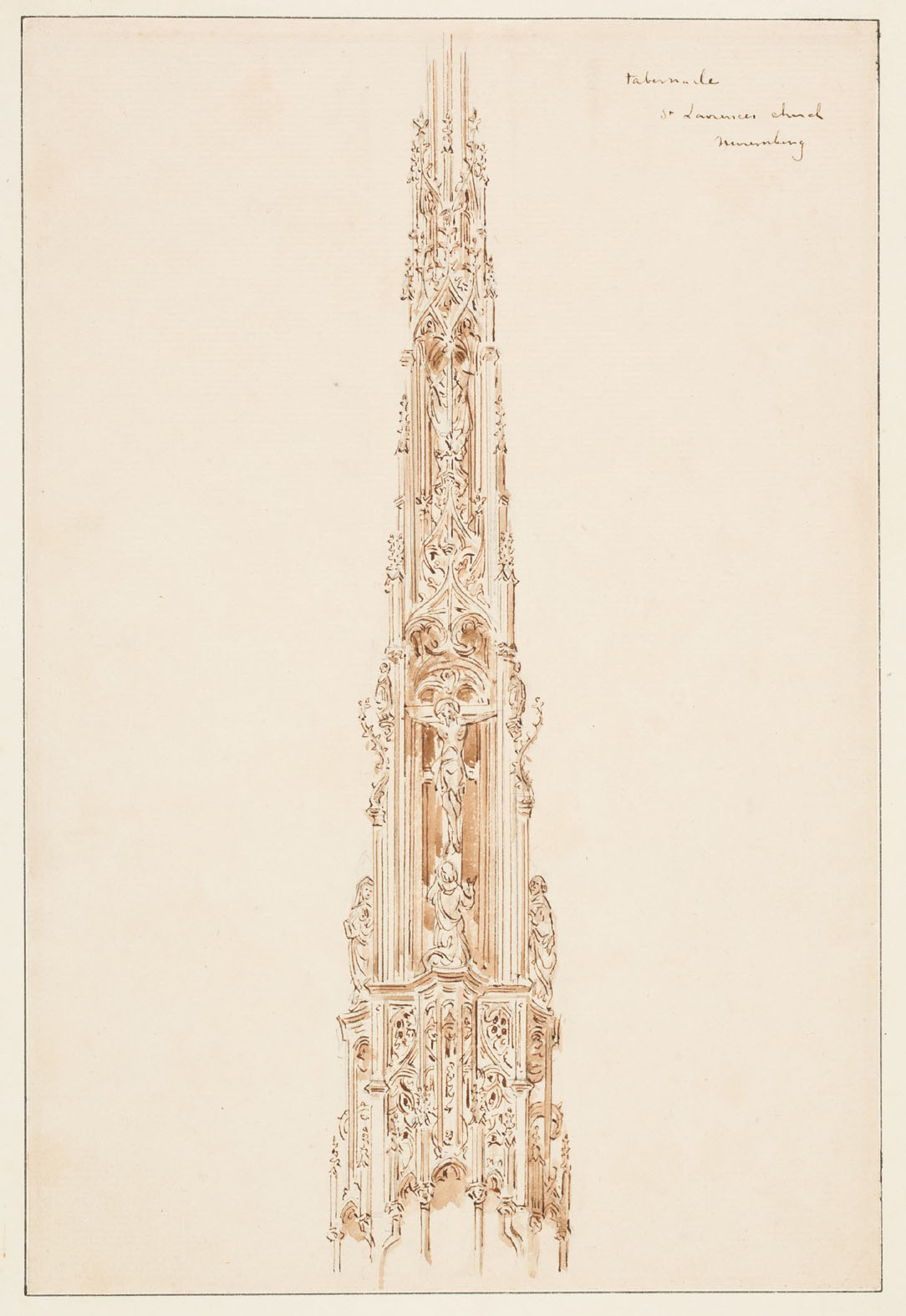

Much the most famous of the late medieval buildings in the city is the Church of St Laurence to which a soaring late Gothic choir, with star-ribbed vaults, was added between 1439 and 1477. A ladder would have been no use to Pugin here yet he was instinctively drawn to record the astonishing pinnacled tabernacle, which abuts one of the eastern piers in the choir.

This is not a tabernacle, as we understand the word today, but an extensive Gothic balcony on which at least ten people might stand with a tiered canopy of filigree Gothic pinnacles containing scenes from the life of Christ and rising the full height of the vault. Soaring to more than eighty feet, I can hardly imagine how Pugin drew it: looking up high to see what he had to draw and then shifting his focus to the sheet of paper – back and forwards again and again.

He had to split his drawing between two pages to fit the whole monument in. The tabernacle is the work of the master sculptor, Adam Kraft who took three years to complete it in 1496. Kraft is a leader among German Renaissance realistic sculptors, a man of brilliant imagination who, in a wonderful stroke of bravura, placed a life-sized figure of himself, with jutting black beard and a mason’s mallet and chisel in each hand, crouching beneath the centre platform of the balcony to give support to it. Pugin catches all these details as well as the filigree spire.

Like a lot of architects he was not very good at drawing people. The figure of Kraft is unconvincing in Pugin’s sketch, and his attempt at the ‘Schone Madonna’ of 1285, a beautiful figure of the Virgin and Christ Child on a bracket in the nave, has none of the grace of the original. The statue of the Archangel Michael in Pugin’s hands becomes an awkward jagged figure with angular wings and an unwieldy sword.

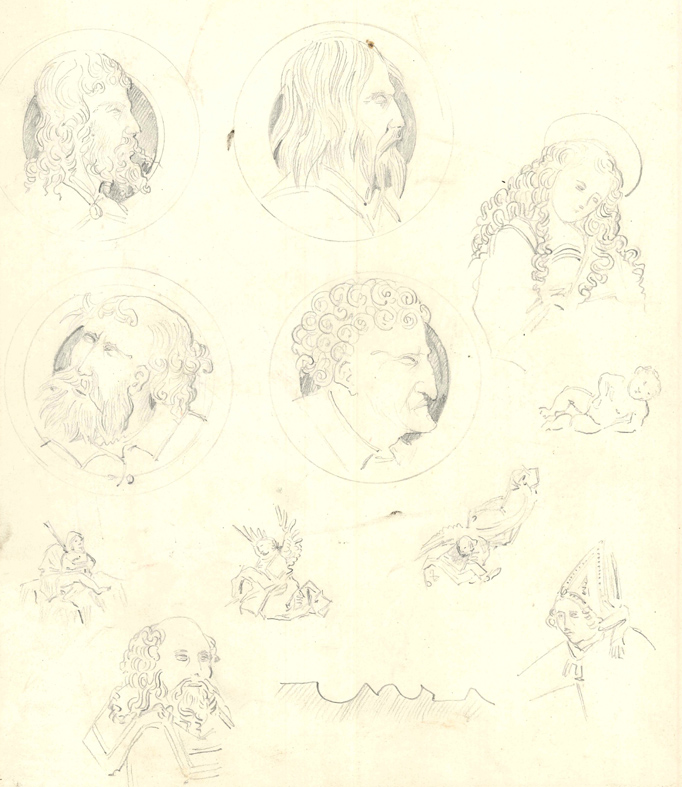

Even so, if he was better at drawing buildings than bodies, critics from his own time to the present day have always admired the fluency and facility of Pugin’s hand. Whether he is drawing with a finely sharpened pencil as at Stirling, or in sepia ink touched lightly with wash as at St Laurence’s church in Nuremberg, Pugin’s line is never dead. It has the quality of a life of its own, strong and firm in one place – even emphatic – so that at times the pencil almost bites into the paper or the ink is full and dense, only to fade to a fragile line which is allowed, at times, to die away completely the better to model the forms on the page. David Hockney in a different age is a master of this same sort of graphic economy. We can see it particularly well in Pugin’s drawing of a number of figurative corbel stones from Stirling Castle or in the curious studies of decorative portrait heads set within circular bands whose source is unknown. This is rapid, un-laboured draughtsmanship, employed with urgent immediacy by a man who never seemed to rest.

We should remember however that Pugin could never have expected that these slight drawings would be put on public display. For him, they were simply part of the office equipment, essential as source material to feed into – or perhaps at times to nudge – his creativity. Two hundred years earlier Rubens had used his own collection of drawings, thematically arranged, in exactly the same way. For both artists the drawings were a means to an end, not an end in themselves.

It was Pugin’s intention to revolutionise attitudes to architecture in Great Britain and Ireland and in large measure he succeeded in his objective. Outside the Architecture Gallery room and hanging in the stair hall of the Archive is a large gilt-framed perspective drawing of Cobh Cathedral designed by his son, Edward Welby Pugin then in partnership with Pugin’s son-in-law George Ashlin. Below it on a table in the hall is an architectural model of Rawson Carroll’s big Gothic church, with its splendid broach spire, built at Leeson Park, Dublin, for the Molyneux Institute. Each of these Irish churches is a confident, strong design of real authority. The fact that so many buildings of this character were to be built everywhere in Ireland in the second half of the nineteenth century signals, unequivocally, the triumphant conclusion of Pugin’s personal crusade.

Alistair Rowan,

Dublin, 2018