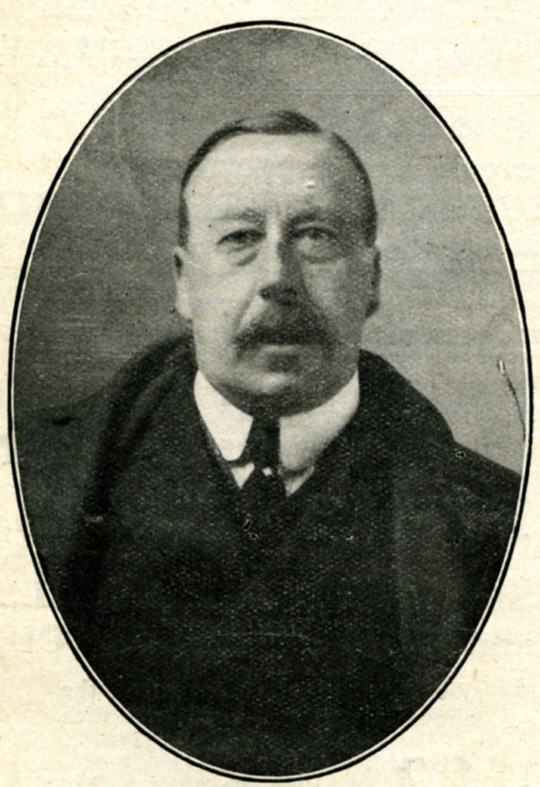

Donal Hickey discusses the Berkeley Library exhibition which he curated in the Irish Architectural Archive’s Architecture Gallery. The exhibition runs until the end of the second week of January 2018.

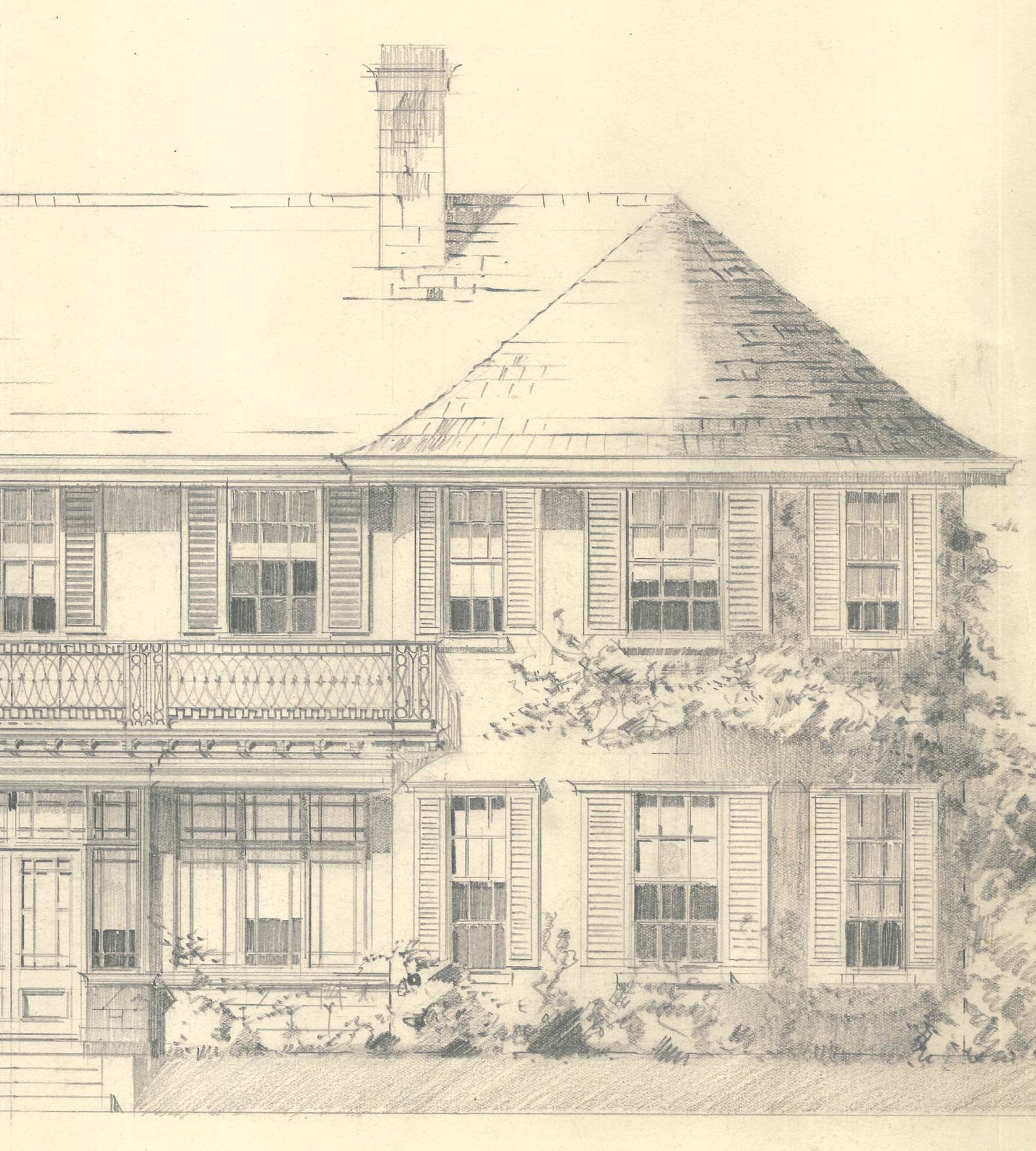

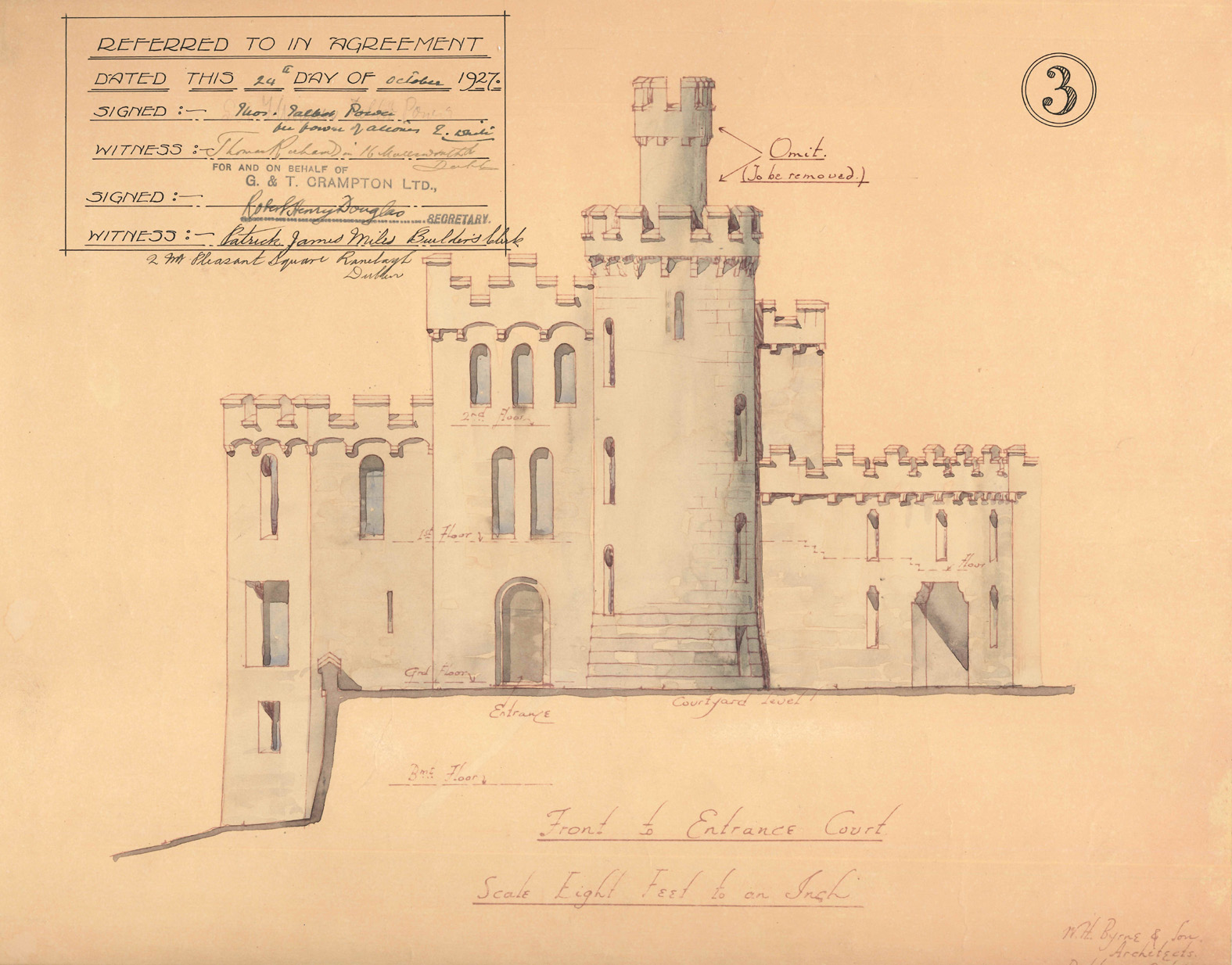

The concept for this exhibition began with discussions with Dr Ellen Rowley when she asked me to look at some material on the Berkeley Library at the Irish Architectural Archive. There I found a small box containing over 280 black and white photographs which begged to be displayed. The images document the progress of a New Library at Trinity College, designed by Ahrends Burton Koralek (ABK) and constructed by G & T Crampton, between 1961 and 1967. From the beginning I discussed this photographic record as a continuous timeline around which a narrative could be constructed to document the evolution and progress of the design and construction of the New Library.

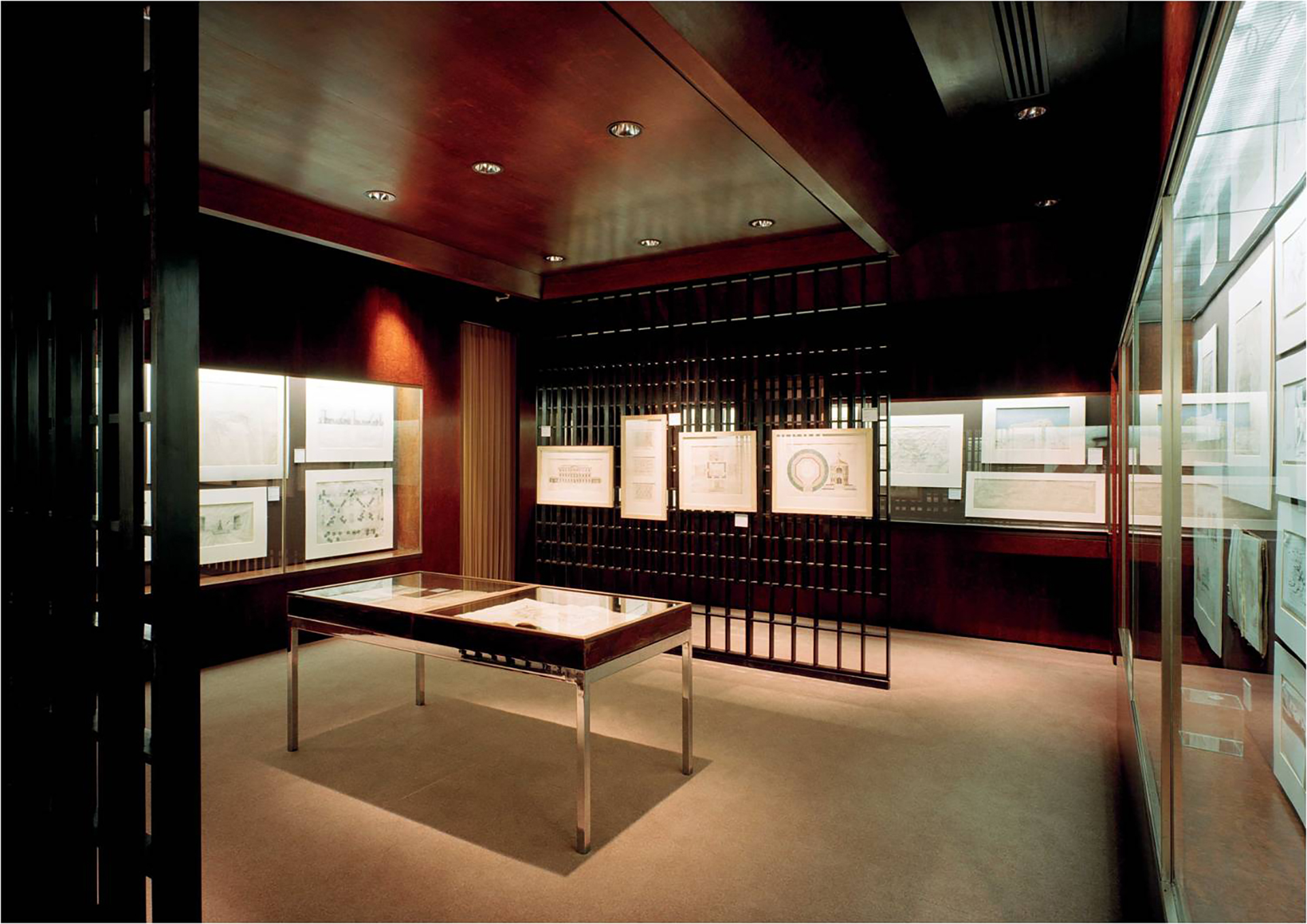

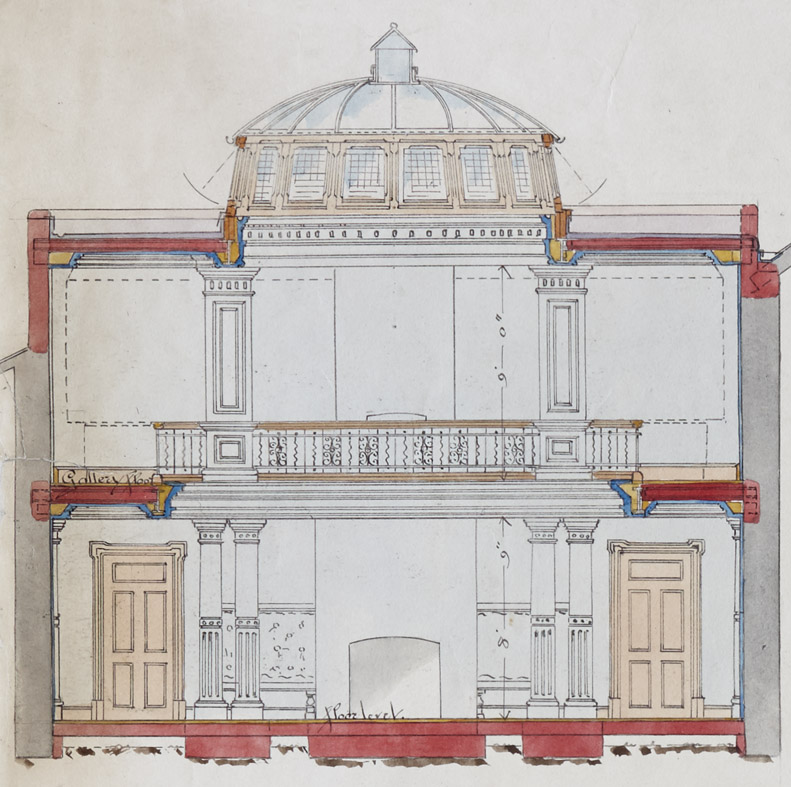

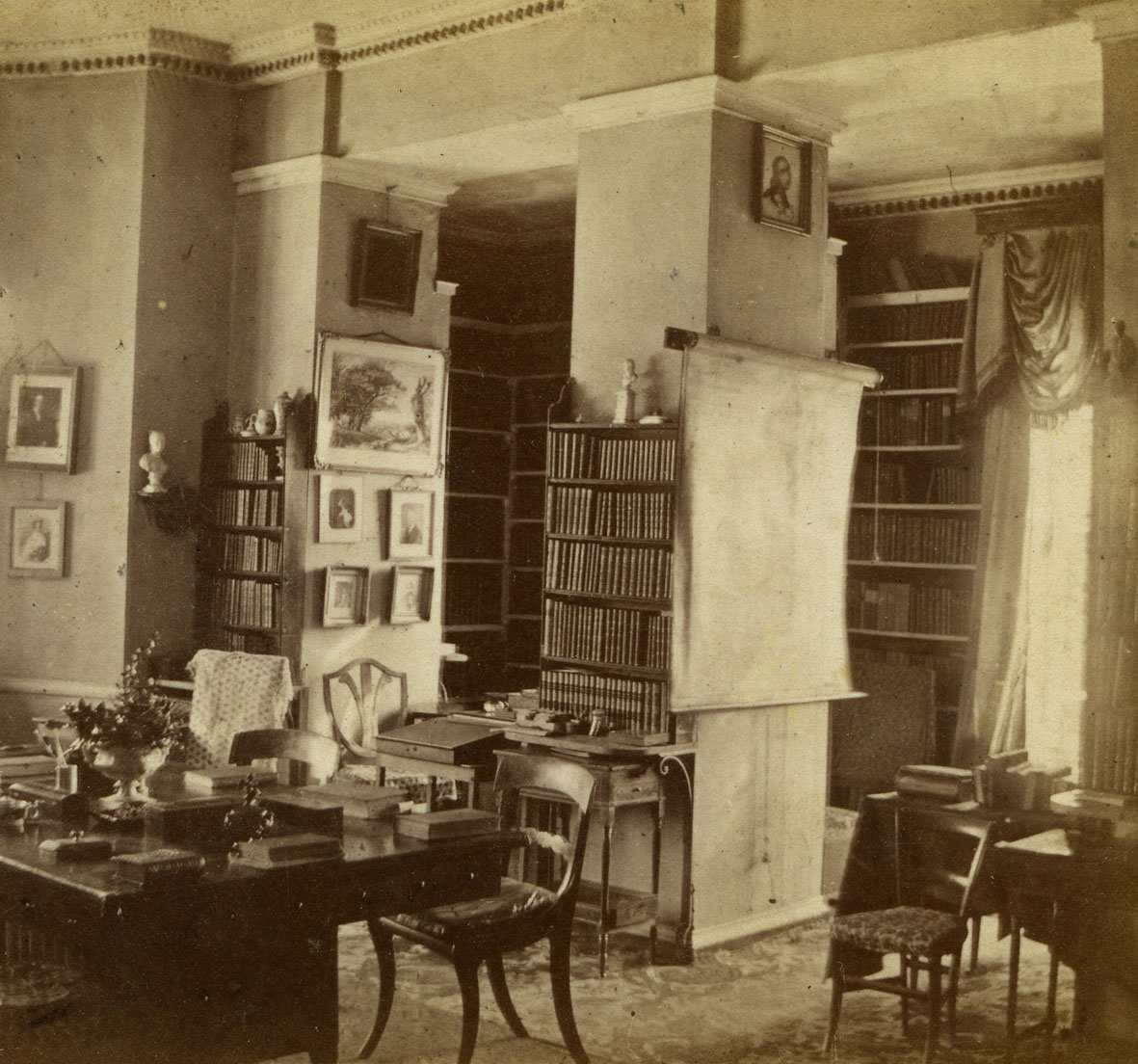

The Architectural Gallery is a room I am familiar with from my time working in London. It had a previous existence as the lining of an exhibition room in the Royal Institute of British Architects at Portland Place. A neat symmetry offered itself as I could now revisit my experiences of London architecture while interrogating the origins and influences legible, explicit or implied in the Berkeley library and the archives at the IAA and Trinity College.

The presentation of this exhibition is intended to be open-ended for you the audience to imagine other connections beyond those illustrated. Even now as I write I am adding other clues and references which might assist a more complete reading of the design process and its complex influences. It is not hard to imagine the fervour and intensity of ABK’s collaboration which is evident in the final building and explicit in the selection of sketches and drawings of various versions of the project. Architecture is their gift: a silent legible mechanism, a conduit for our experience.

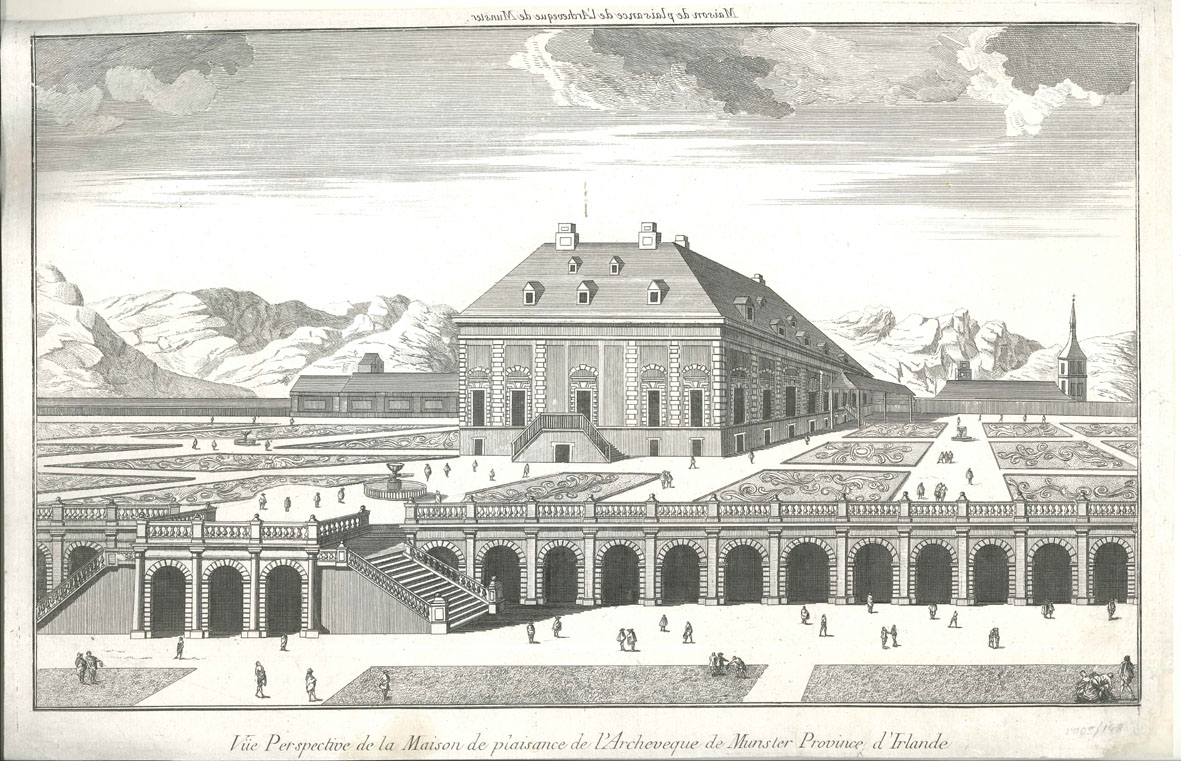

As in the game of chess, where the knight’s move allows a piece to move in an unorthodox fashion relative to the other pieces on the board, combining the orthogonal and diagonal directions to shift across both plains, the Berkeley tilted the spatial game in Trinity College, introducing a dynamic relationship with the traditional order of the campus.

Donal Hickey

December 2017

The full catalogue of the Berkeley Library exhibition is available here: https://iarc.ie/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Berkeley-IAF-Pamplet-FINAL.pdf

The Berkeley Library exhibition continues in the Architecture Gallery, Irish Architectural Archive, 45 Merrion Square, until Friday 12 January 2018.

The Architecture Gallery is open to the public from 10 am to 5 pm, Tuesdays to Fridays.