Dr Rachel Moss is Assistant Professor in the Department of History of Art and Architecture, Trinity College Dublin, former board member of the Irish Architectural Archive and current President of the Royal Society of the Antiquaries of Ireland. In February 2016 she graciously agreed to open an exhibition of photographs of Dublin after the 1916 Rising taken by the antiquarian Thomas Johnson Westropp who had held the RSAI Presidency in 1916. This blog is based on her remarks on that occasion.

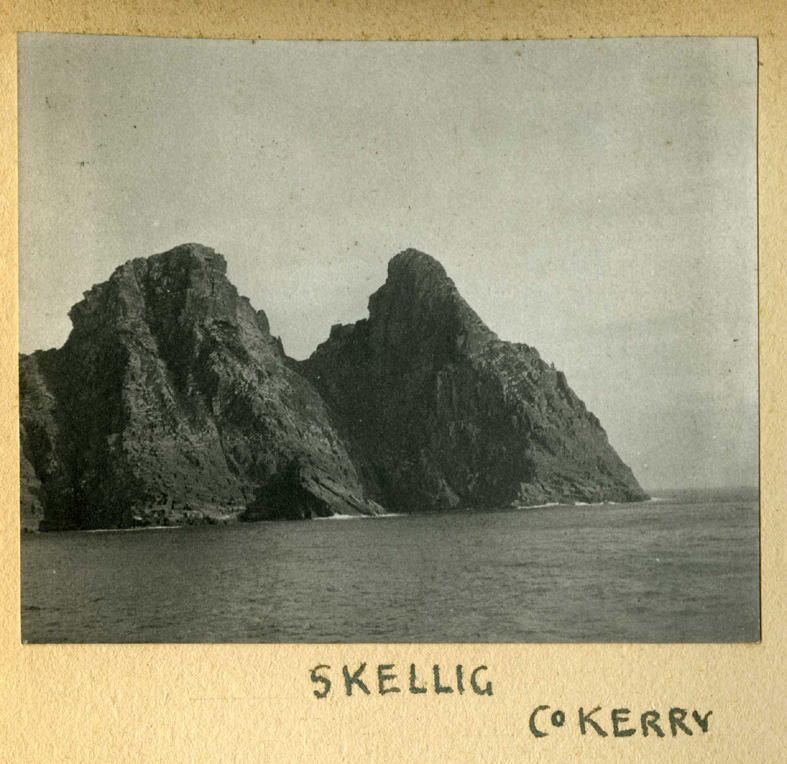

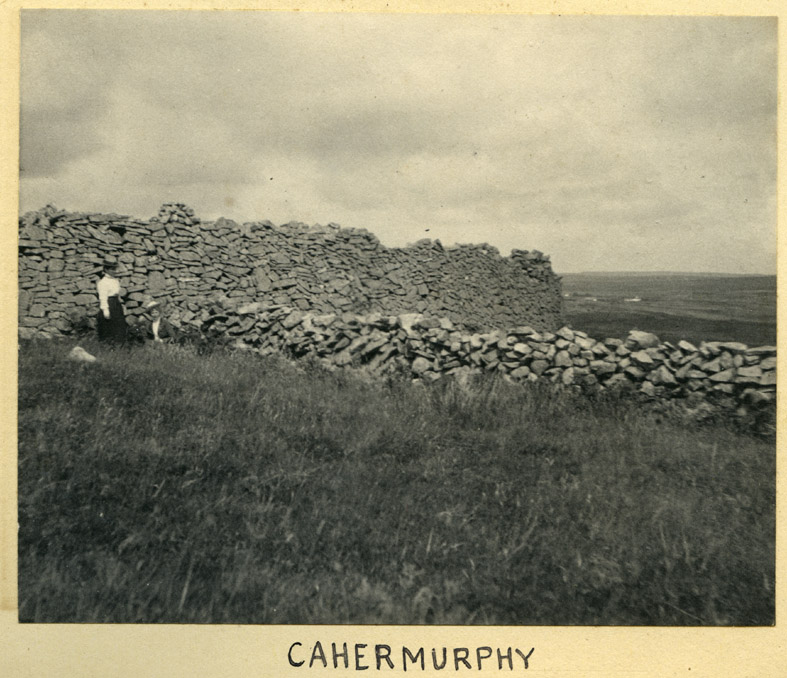

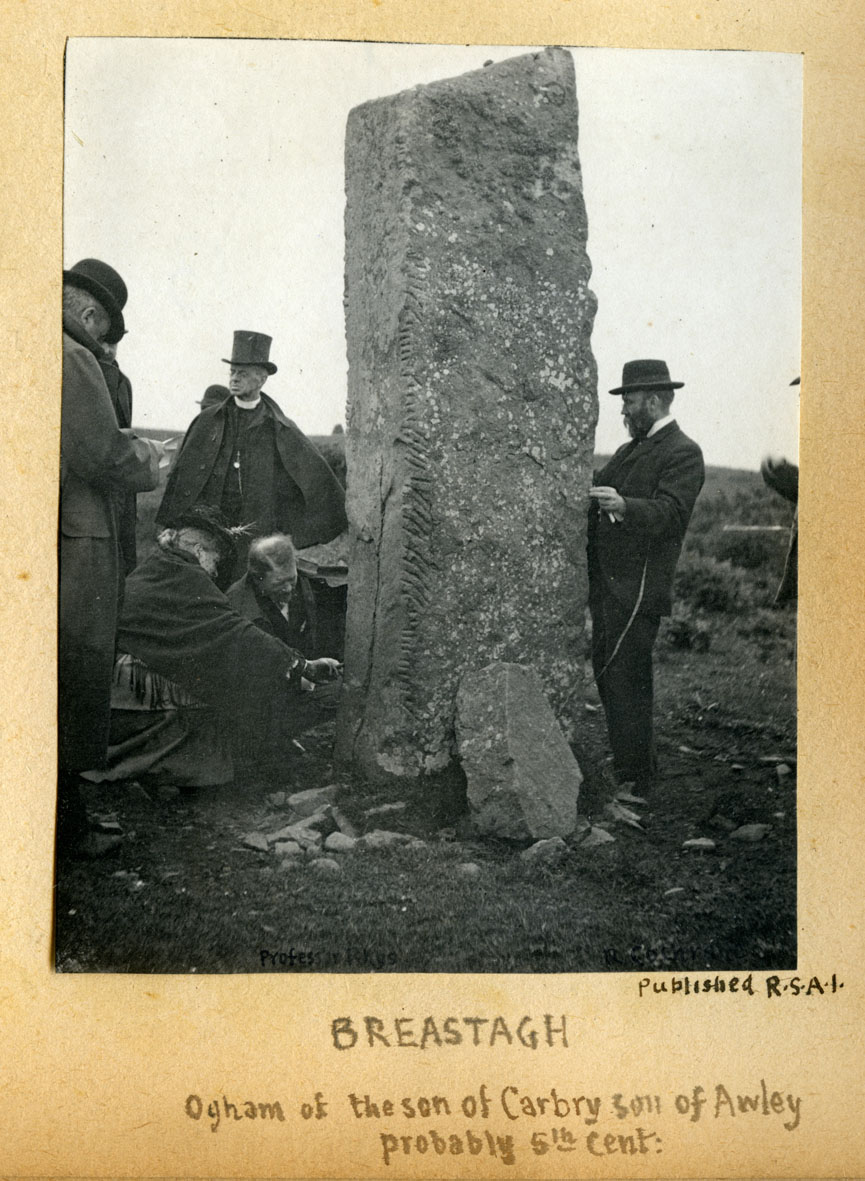

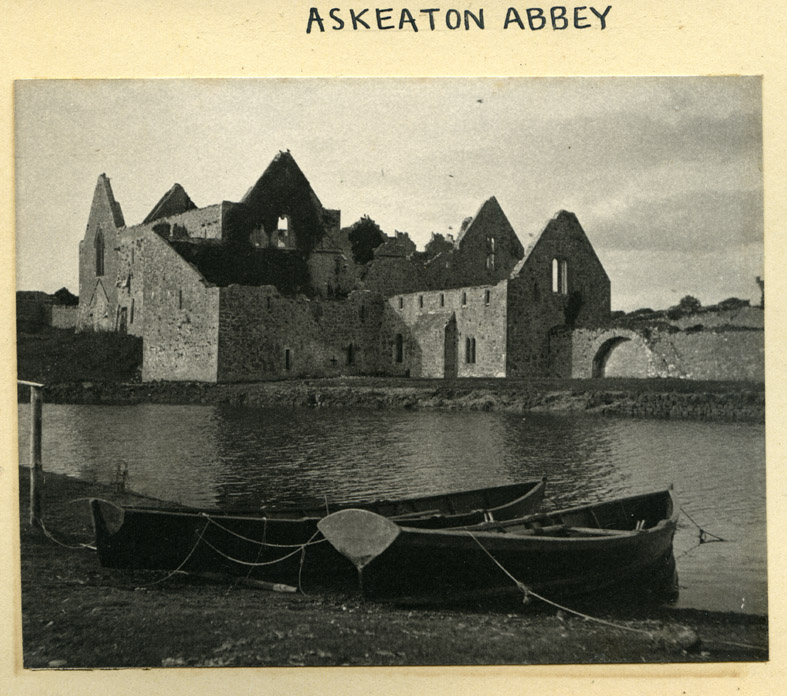

A civic engineer by training, Thomas Westropp had fostered an interest in architecture from an early age growing up in Limerick. From 1888 (at the age of 28) he was a regular contributor of articles on Irish antiquities to a variety of journals, and these were invariably densely illustrated with his own sketches and photographs. Like many of the antiquarians of his generation, he was keenly aware of the high rate of attrition of ancient buildings in Ireland, and was particularly keen on the use of photography as a method of accurately recording structures that were in danger of being lost. He saw his antiquarian work not only as historical enquiry, but a race against destruction, wrought, as he identified it in the late 19th century, by the ‘deadly triad’ of the road maker, rabbit catcher and treasure hunter.

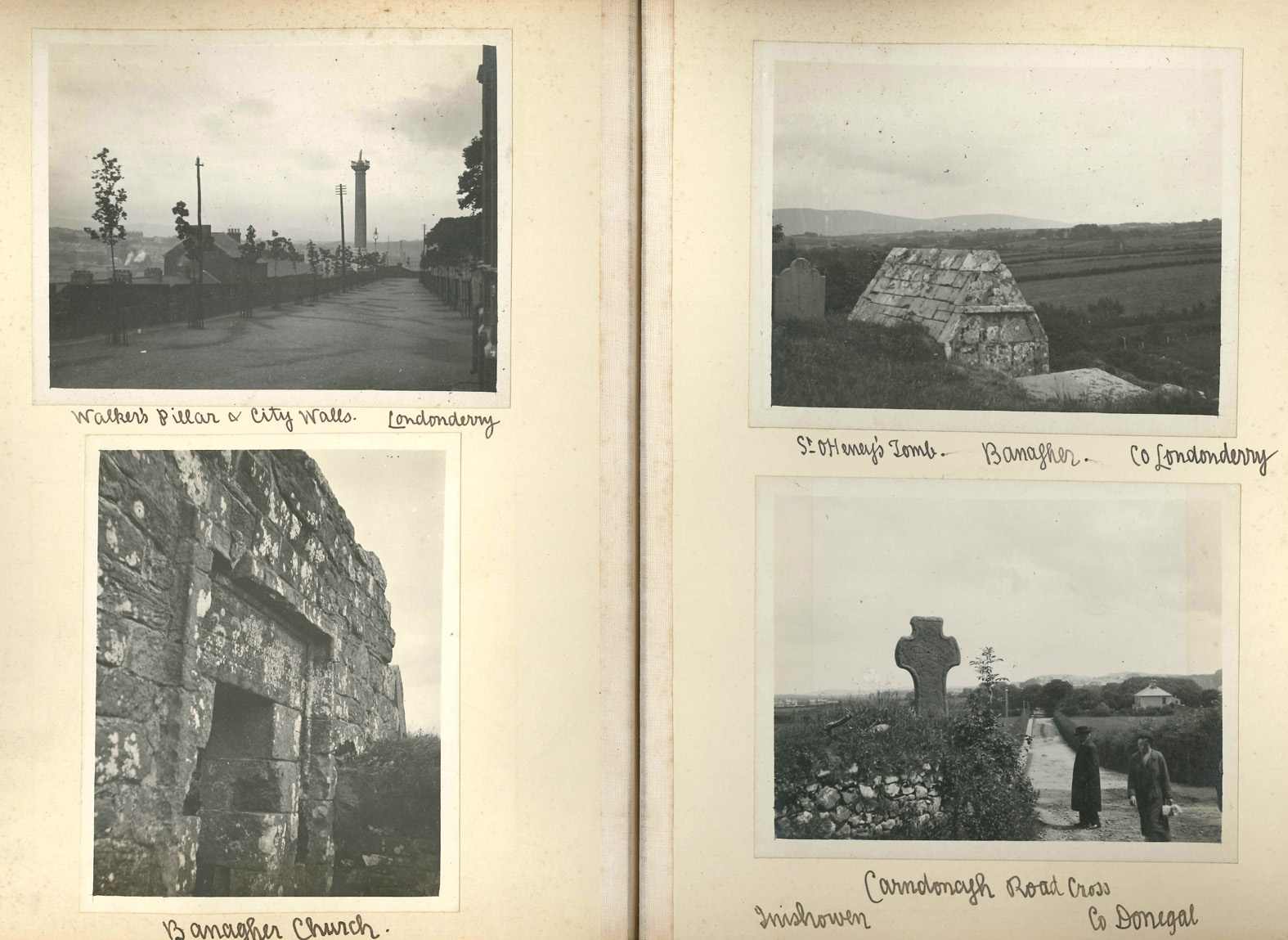

With this in mind he took on the role of curator of the Antiquaries photographic survey from 1894, encouraging members to deposit photographs made using permanent processes that recorded the field monuments of Ireland. By the 1910s, there was a healthy flow of dolmens, crosses and ruined churches and castles streaming into the Society’s collections. The photographic skills of members were not just reserved for pre-historic and medieval buildings. Several active members participated in the recording of Georgian Dublin under the auspices of the Georgian Society, with Ephraim McDowell Cosgrave later depositing his photographs from that survey with the Antiquaries. And the photographic skills of Council member John Cooke were applied to the documentation of housing conditions in the Dublin tenements following the Church Street collapse in 1913, images that were also to join the collection curated by Westropp.

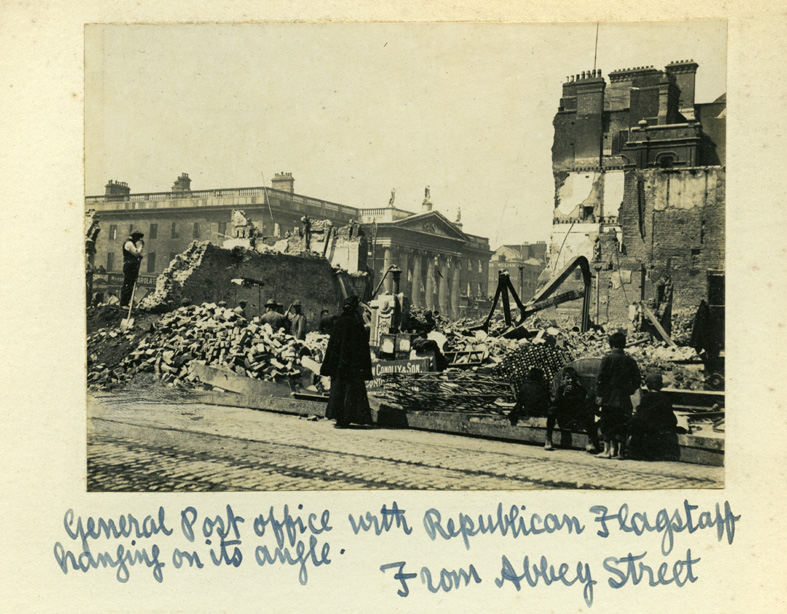

With this track record for documenting the vanishing past, one might expect that Westropp’s post-Rising photographs were taken at the behest of the Society. After all, both in terms of property and personnel it was far from aloof of the events of Easter week. The Society only purchased 63 Merrion square in July 1917, and in April 1916, their premises and collections were located at no. 6 Stephen’s Green (now Top Shop), neatly sandwiched between the action in the College of Surgeons and the Shelbourne Hotel, where over 100 British soldiers had been stationed during the rising. Westropp had only taken over as President in January of 1916, stepping into the shoes of Count George Noble Plunkett, father of Joseph Plunket who was executed on 4th May, just two weeks prior to Westropp’s photographic excursion. Among the list of new members admitted to the Society at its January 1916 meeting was a certain Thomas McDonagh, and the Hon. Gen. Sec. at the time was Charles Mc Neill, older brother of Eoin McNeill, (the latter who himself would become President of the Society in 1937).

Yet apparently, the Society was not directly involved in the commissioning of these images. Copies of the photos were deposited with the National Library of Ireland, Trinity College, the Royal Irish Academy and were contained within the albums now in the Irish Architectural Archive, but none made it to the Antiquaries photographic collection. Indeed reading through the correspondence and minute books in the months surrounding April 1916, there is almost an unnatural silence regarding what were referred to as the ‘gloomy and critical’ times in the Society’s journal of that year. Instead, the principal preoccupations that emerge around the time are arrangements for the summer excursion to Limerick. Thus there are endless letters penned by Charles McNeill on what kind of tea the group might expect to get for a shilling a head in the Dunraven Arms and various other hostelries in the area, and a good deal of toing and froing on the number of chara-bangs that were going to be required. There is also a request to the inspector general of the RIC for permission for the group to travel to Limerick. This was granted on condition that no photographs or sketches were made of Limerick castle, or any part of the Shannon estuary south of this.

In his earlier writing on the antiquities of the Clare, Westropp had expressed his exasperation at the emerging nationalist movement and the lack of importance that it placed on the past. Writing on the prehistoric remains of the Burren he commented ‘so little does the professed patriotism of the men of Clare bear fruit in the care for or preservation of their country’s past, that since I began my work on the county, the ruin of its remains is alarming’. He was also critical of the Romantic view taken by some nationalists who ‘glorying in their country’s early legends’, resented the work of more critical ‘workers’. It was by hard work, Westropp asserted, not by ‘exaggerating things that never happened’ that the ancient glories of Ireland would be secured.

Sticking to the truth, the facts, was something for which he received criticism in his writing, the author of his obituary commenting on the dense forest of facts that confronted the reader of his articles. But so it was, in the impartial spirit of the archaeologist, rather than the critical liberal unionist, that he took the Dublin photos. The short captions that accompany the photographic prints convey no sense of Westropp’s feelings about what had happened to the centre of his adopted city. He points out the flag staff of republicans on the corner of the GPO, but otherwise information is limited to the location at which the photograph was taken. This is the presentation of the facts. The rights and wrongs of what had happened was left to the individual viewer’s own interpretation.

It is only in a footnote, added to his presidential address of January 1916, that Westropp alludes to the ‘utmost risk’ to which ‘our libraries, museum and records office’ had been exposed during the week’s warfare in Dublin. Perhaps it was for this reason that he distributed copies of these important photographs to a number of repositories around the city. Either way, we owe him a debt of gratitude for his endeavours.

Dr Rachel Moss

February 2016