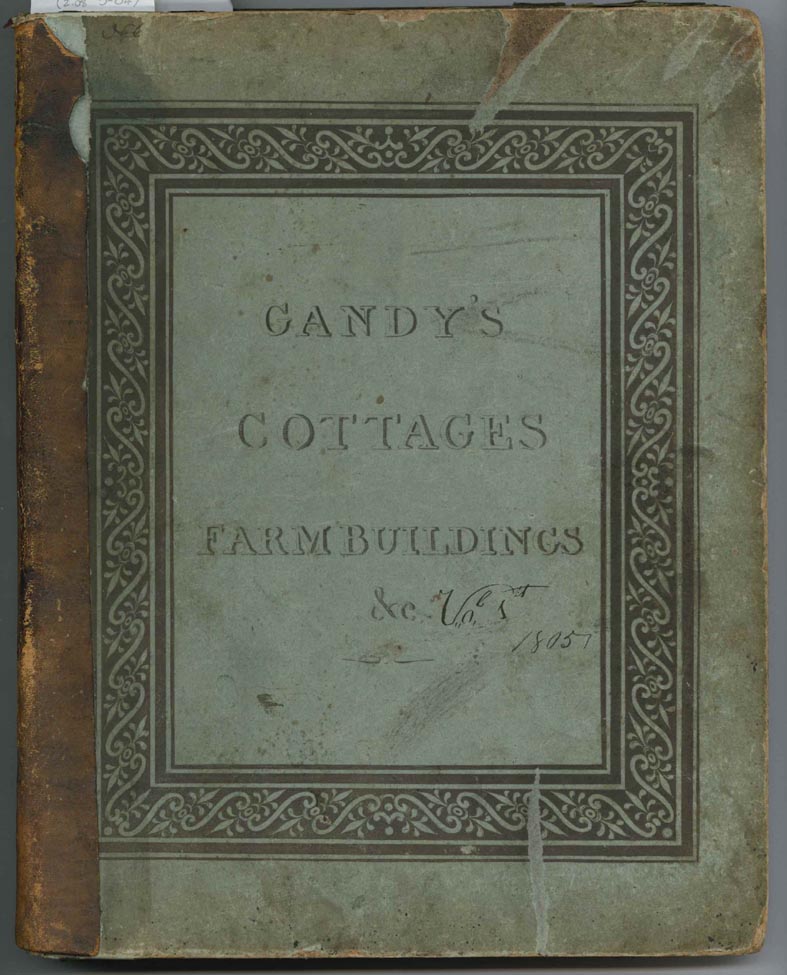

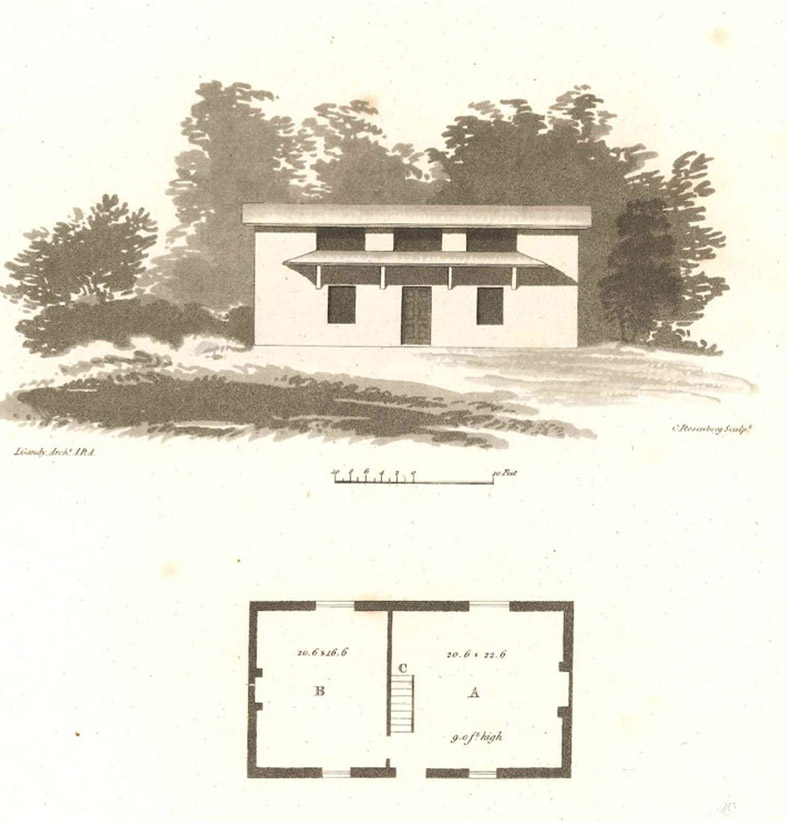

Recently the architectural critic Shane O’Toole donated to the Irish Architectural Archive a book which had belonged to his father, a copy of Designs for Cottages, Cottage Farms and other Rural Buildings, published in 1805 by the English architect Joseph Gandy (1771-1843). This ostensibly simple work contains page after page of designs, some of them deceptively modern in appearance, displaying ideas for ‘modest’ country residences. It is an important addition to the growing collection of architectural pattern books held by the Archive.

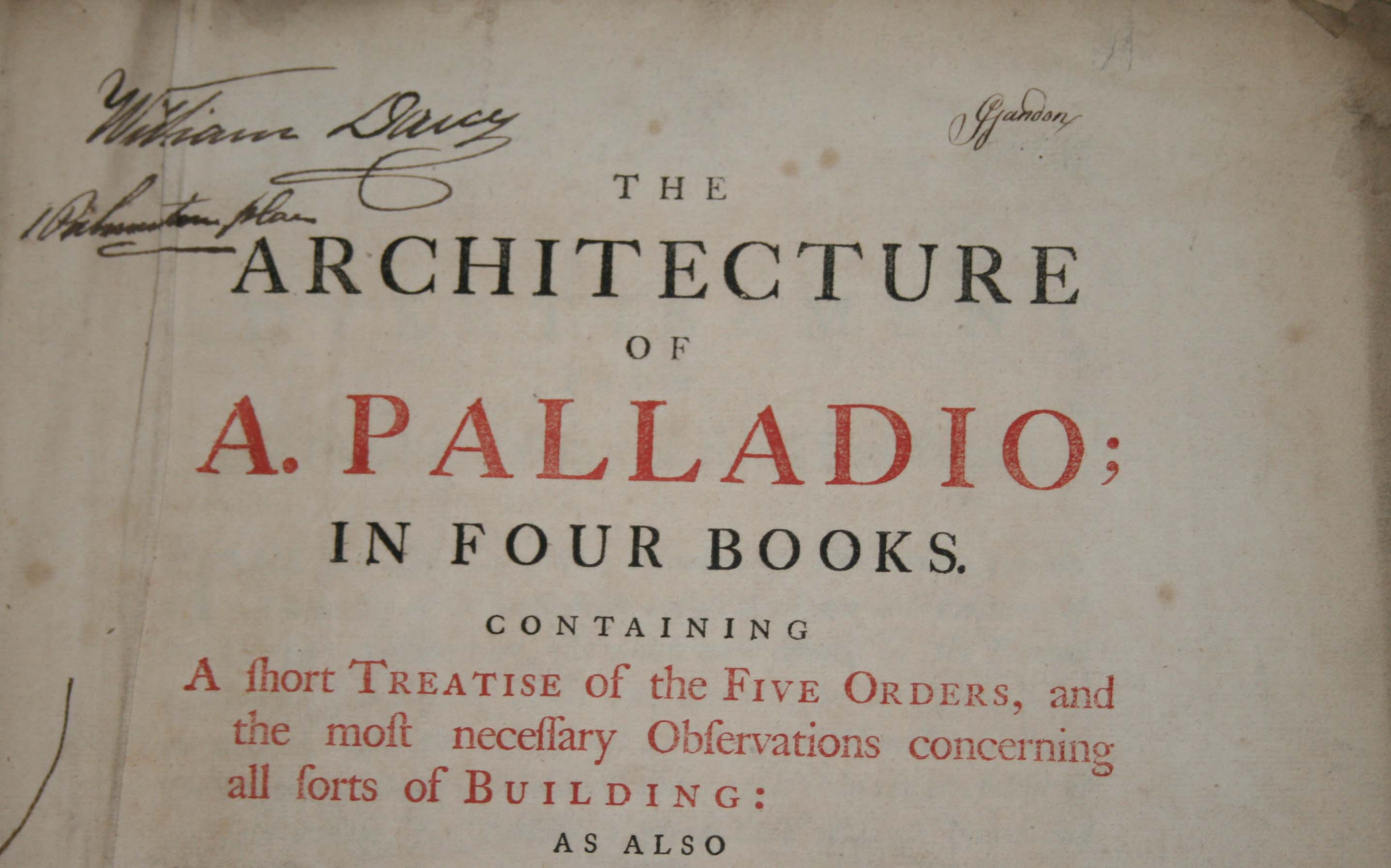

The history of the pattern book is a long one. Its origins can be traced to the Ten Books on Architecture of the Roman architect Vitruvius (c. 80-70 BC). However, the idea of pattern books really came of age with the publication of I Quattro Libri dell’ Architettura (The Four Books of Architecture) by Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) in 1570. Villas and palazzi of refined elegance and beauty were displayed on his pages, and through the wide dissemination of the book, available from the 1660s in English translations, the Palladian style became an inspiration to architects from Christopher Wren to Inigo Jones to Edward Lovett Pearce. The Archive holds a copy of the 1742 edition of Giacomo Leoni’s translation of the Quattro Libri which once belonged to James Gandon, and later to William Henry Byrne.

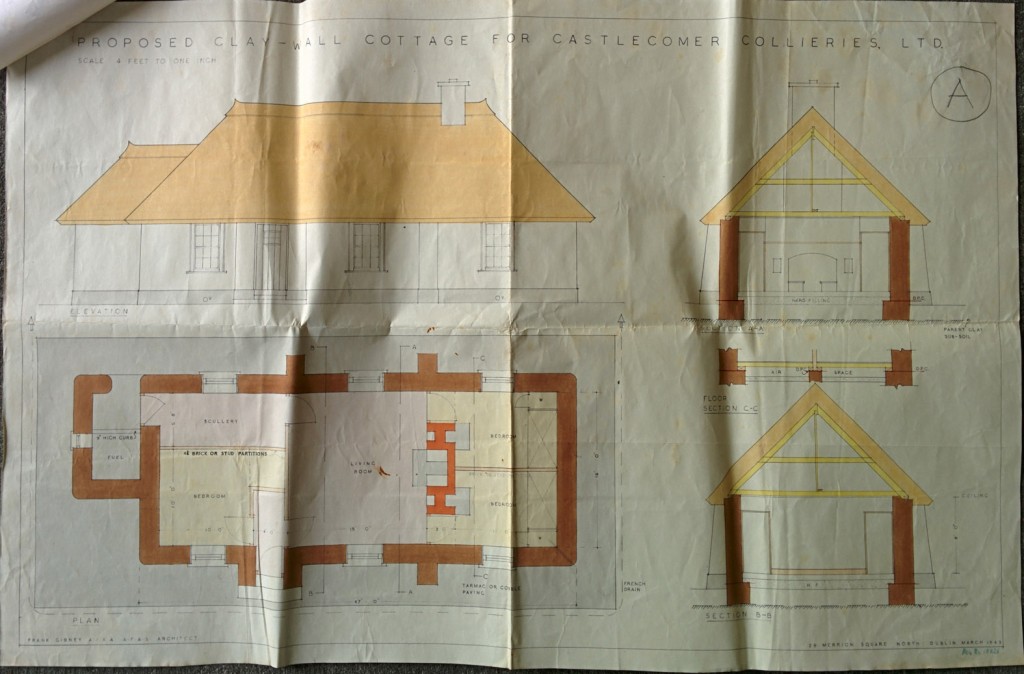

Architectural treatises soon developed into more than discussions on the use of the classical orders for grander houses and public buildings, so that by the late 18th and early 19th centuries they became a means for architects to display their suggestions for more modest buildings. British architects such as John Plaw, Francis Goodwin and John B. Papworth produced books on rural residences, villas, cottage ornée, gate lodges, cottages and farm buildings. Irish examples of the genre are quite rare but include Twelve Designs of Country Houses by ‘A Gentleman’, published in Dublin in 1757, and Lady Helena Domvile’s Eighteen Designs for Glebe Houses and Rural Cottages, 1840, all the rarer because of the gender of the author.

Gandy stated in his introduction to Designs for Cottages that he was influenced by a Board of Agriculture publication discussing the need to improve ‘the conditions of the Labouring Poor’. He notes that ‘we should combine convenience of arrangement with elegance in the external appearance’, and says his designs are ‘offered as hints for the consideration of Country Gentlemen, and others, who build, and who are sufficiently aware of the use and importance of consulting Architects upon these occasions, by which disappointment, and eventually great expenses, may be avoided’. For Gandy, the pattern book is an architectural calling card, advertising an architect’s abilities and encouraging potential patrons to seek out his professional services. He never intended that anyone would actually build from these published drawings.

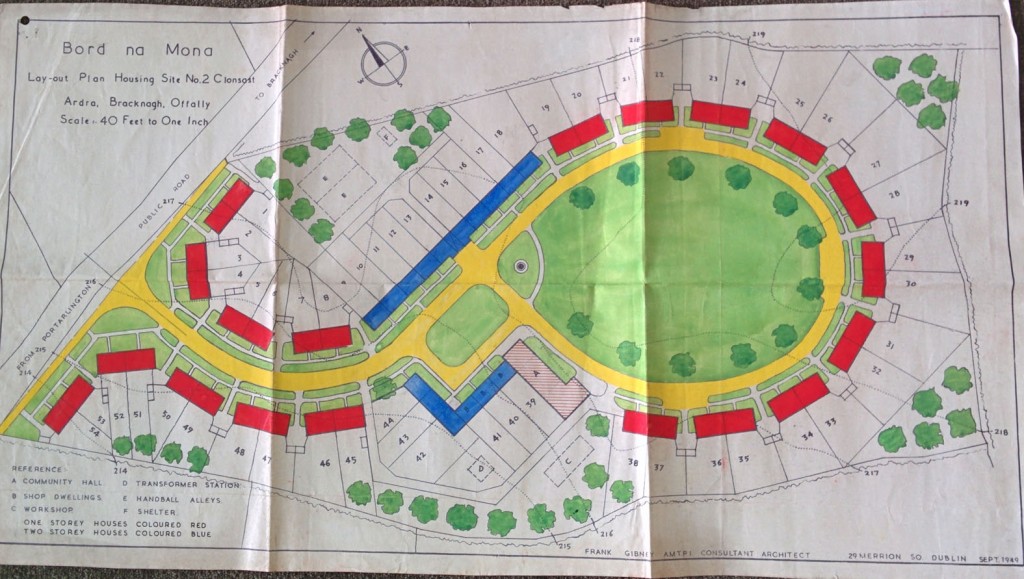

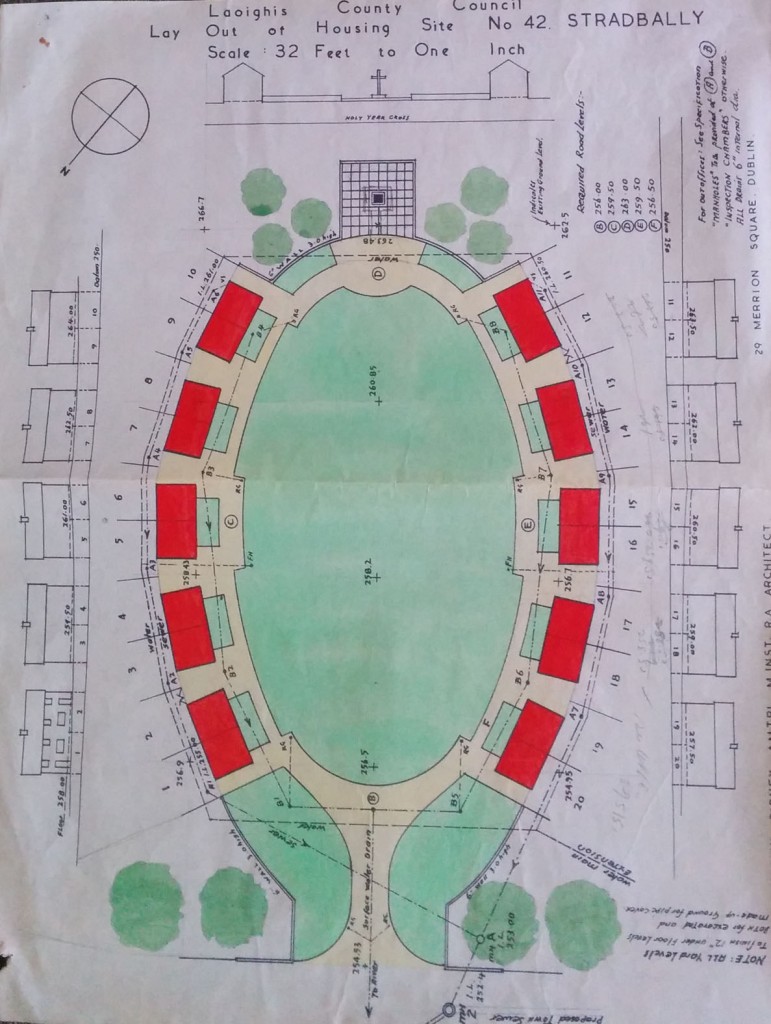

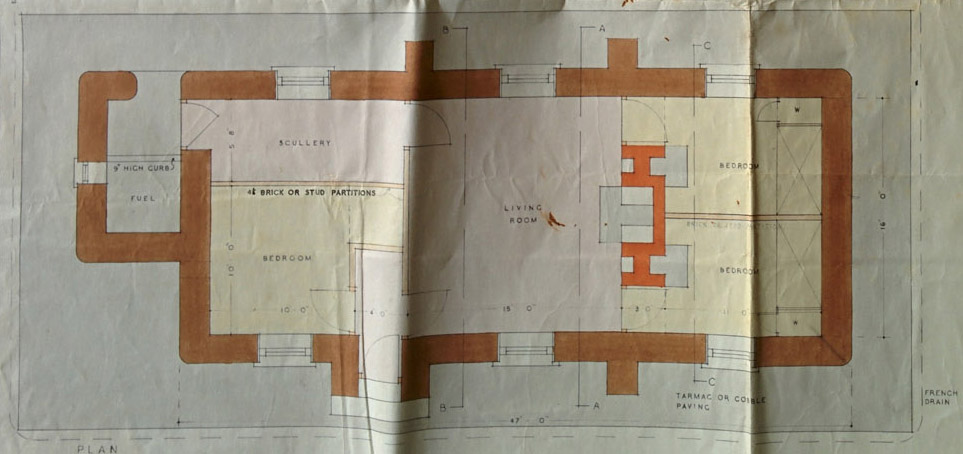

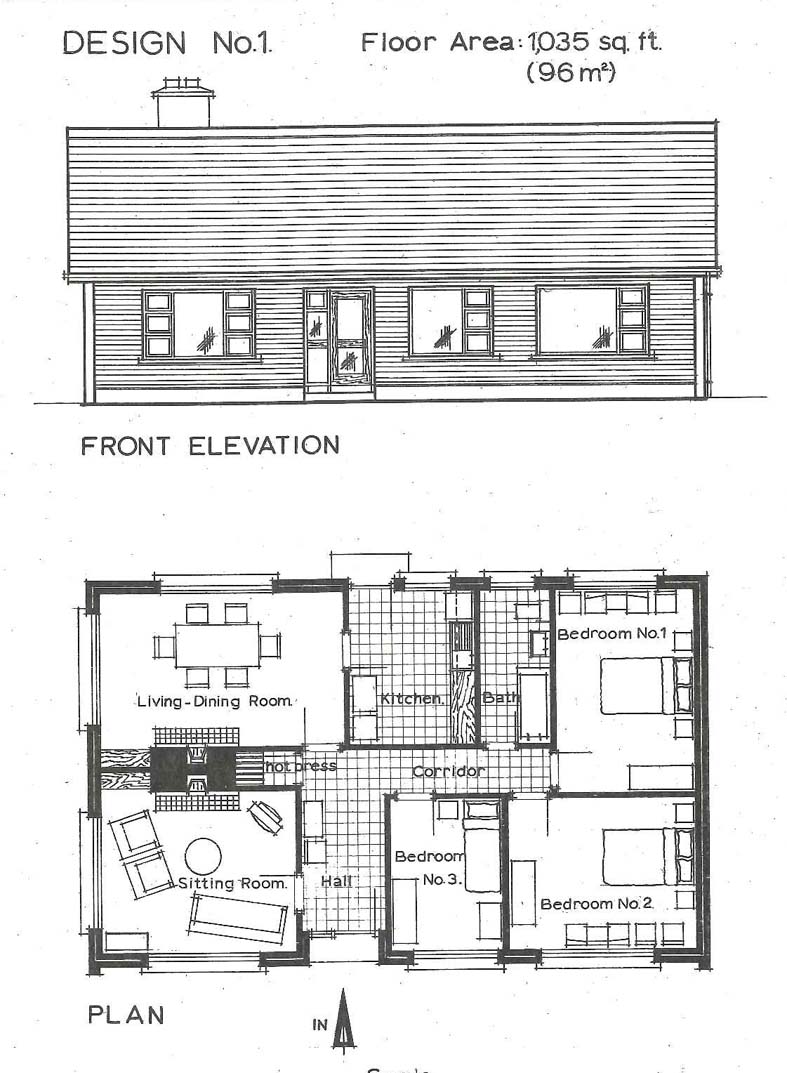

Guides, manuals and pattern books didn’t die away after the 19th century, and thanks to another recent acquisition here at the Archive we are reminded of that. In 2013, Jack Fitzsimons placed in the Archive a set of each of the published editions of his seminal Bungalow Bliss, a series of design books that served as a template for so many houses in the Irish countryside, later donating many of the original drawings for the first edition. From 1971 to 1998, through at least twenty-six reprints and twelve separate editions, Fitzsimons’s books included drawings, details of services, information on grants, town planning, contracts and decoration for modest two- to four-bedroom homes. For a fee (£10 in 1970) the full set of measured drawings and specifications could then be ordered. Robert Molloy TD, the Minister for Local Government, noted in the introduction to the first edition that, while property developers provide housing for the urban dweller, for the rural and small town resident the site, design and construction of a house had to be done ‘on his own initiative’ and therefore help was needed. Fitzsimons added that ‘while [the book] is intended primarily for those with little or no knowledge of the subject it is hoped that it may also prove a useful reference book for those already engaged in any sphere of housing’. Here was a pattern book from which the author did intend people to build. And build people did.

Aisling Dunne,

Irish Architectural Archive,

October 2014.