In the Archive Blog last month we read about the work involved in identifying an unknown house in an old photograph brought in to us by a member of the public. Furthermore, thanks to Aisling’s intricate detective work, we learned about the history of a pair of houses in Glenageary, ‘Sharavogue’ and ‘Kilcolman’, one now long disappeared, and we were shown a tantalising glimpse into the lives of those connected to the two houses.

Here in the IAA we also have our own small collection of waif and stray images: photos of street scenes, buildings and ruins, all waiting to be reunited with their identity. These photos have been gathered over the course of the lifetime of the IAA, and we like to revisit them every so often and see if we can progress any further in our efforts to identify them.

As with all researchers using the Archive, we can follow standard steps as part of the process of researching the history of a building. In addition to the use of long-established methods and sources, the progress of research has of course been revolutionised by the internet. As well as a straightforward Google search, the use of Google Street View has transformed our capability to trace the identity of elusive buildings and streets. Suggestions of potential locations – no matter how far-fetched – can be tried and tested within moments.

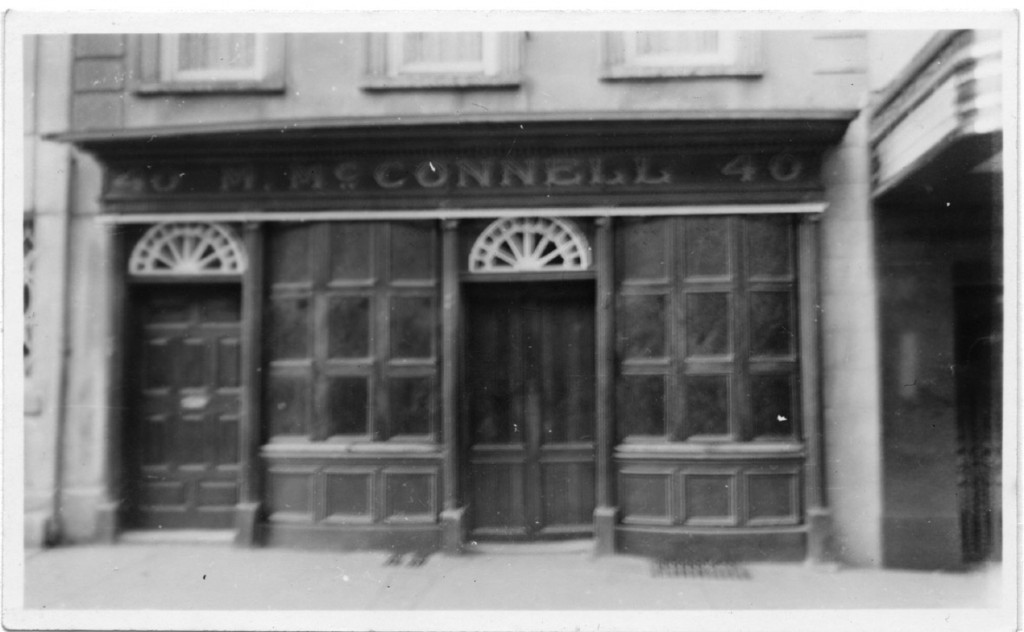

Following in the theme of our current exhibition, Dublin Shops, we have here a small selection of images related to the subject of shops.

Our first enigmatic image was ultimately solved within seconds by the speedy internet skills of Anne Henderson here in the Archive. Unusual surnames can be a very useful starting point and we seized upon ‘C. Colbert Grocer’ in the hopes of a possible clue. Although a simple Google text search for the name yielded nothing, the same query through a Google image search immediately led us to the discovery that this was indeed North Main Street in Youghal, Co. Cork. Further confirmation followed via Google Street View where, a century of change notwithstanding, we could still see the marked projection of the ‘Lynch’ premises in the distance which remains to this day (http://bit.ly/1mFa3aB). However, the distinctive ‘Dutch Billy’ gable front of ‘C. Colbert Grocer’ (so evocative of Youghal’s ancient and important history) has sadly disappeared without trace.

Our next image we think might be of Main Street, Ahascragh, Co. Galway. We think this because of its provenance as part of the Clonbrock Photographic Collection, copies of which are held here in the IAA. Although we can see Monaghan and J. Byrne shops, unfortunately the photo is just not quite clear enough to make out the detail of the street fronts, roof lines and gables. Even Google Street View cannot always solve our mysteries: here it is just not possible to replicate the broad angle of the original photograph and so, until we get further evidence, we are for the moment unable to confirm this tentative attribution. We think it dates from the late 19th Century but we would welcome any suggestions from historians of costume about the distinctive knitted shawls worn by most of the women. We can see a busy market day scene: there is considerable interest in whatever is being sold on the street outside Monaghan’s shop. Once again, we would welcome any insights from our readers.

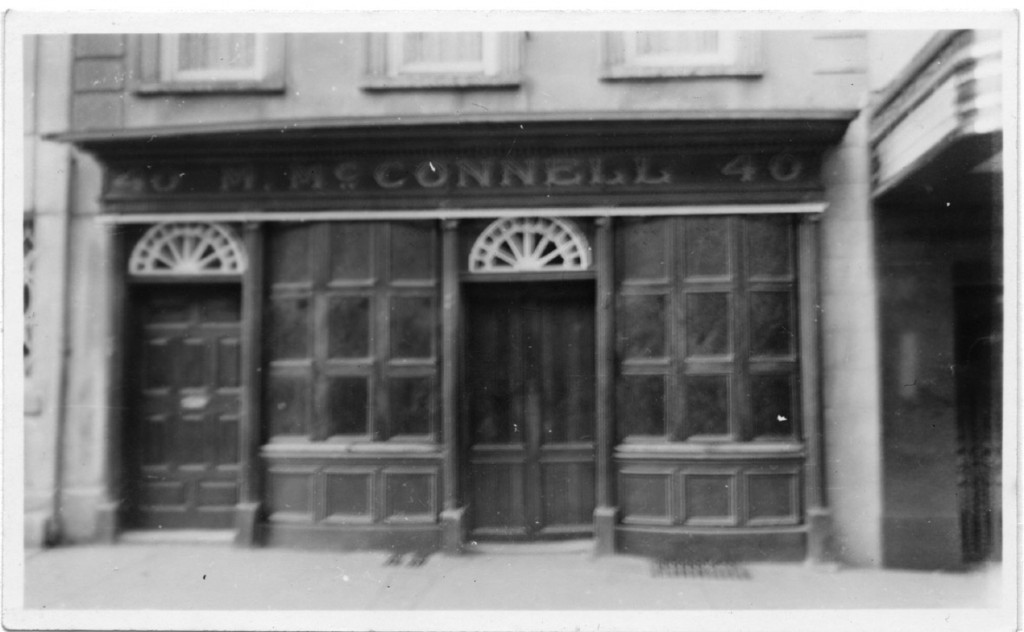

Our third view is of a distinctive urban shop or pub front: that of an M. McConnell, number 40 of an unknown street. Although the facade with its distinctive windows and dual door arrangement looks like an old curiosity shop of the 19th Century, we strongly suspect this photo actually dates from some time in the 1940s. This is for two reasons. Firstly, it is suggested by the provenance and context of the rest collection (all of the rest of the photos in the collection date from this era). Secondly – and more tantalising – is the clue of what looks like an Art Deco style porch, possibly of a cinema, projecting from the street frontage of the neighbouring premises. It evokes what must have been a very notable juxtaposition of contrasting styles of architecture. We checked for an M. McConnell in the Dublin Directories (again the provenance of the collection would suggest a Dublin location), but without any success. Even though Directories can be unreliable, they are a useful starting point, and should always be a first port of call for this sort of query. The absence of an M. McConnell from the Directory could be for a variety of reasons and does not necessarily mean it is not a Dublin building. It just means we haven’t found our building yet.

Our final image is of a shop belonging to a ‘Samuel Davis & Co.’ which appears to be No. 1 on the corner of an unidentified street. It is a handsome shop front and comprises three windows, each framed by barley sugar columns, displaying wares including (as far as we can see) candles, teas, coffees, herbs [?] and spices. Initially it was thought that the building might be at the junction of Baggotrath Place and Baggot Street Lower (the former H. Williams, now Tesco supermarket), but the street numbering and occupancy history of the building on that site do not support this as a possibility. The style of slating on the gable wall of the building is a feature quite typically found in buildings of Cork, but our efforts to follow this up in Cork Trade Directories has not yielded an answer either. Using the Dublin Directories to search by name and trade, we find a possible candidate appear from circa 1883: a ‘Samuel Davis & Sons, tea merchants, 17 & 18 High Street & 11 Rood Lane, London’. However, that leaves us with an unsatisfactory discrepancy in street numbering which does not tie in with our photo. (SEE UPDATE BELOW)

And so we cast our final image before the readers of the Archive Blog, in the hope that we may progress further in our search to find the location of Mr Davis’s shop. In fact, we’re planning to cast many more of these waifs and strays before you in the coming months via our Facebook and Flickr pages in the hope that you will be able to put names to photographs.

In trying to identify images we have learned of the importance of looking out for the smallest of details, the possible clues, and consequent implications they all can give. Nevertheless no matter how searching the eye, there are always some secrets held within photos which will never be revealed. It is therefore appropriate to depart with the biggest mystery of all in this old photograph of Mr Davis’s shop: just who is the woman in the window upstairs?

Eve McAulay,

Archivist,

Irish Architectural Archive,

March 2014.

Identity Crisis Update!

Thanks to the keen eye and researching skills of Dr Alicia St Leger, Cork, one of our anonymous buildings has now been identified as No. 1 Parnell Street, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary.

https://www.google.ie/maps/place/1+Parnell+St/@52.353866,-7.696766,3a,90y,223h,90t/data=!3m4!1e1!3m2!1s2W_o3Bj8UqQ1skjOApN6Zw!2e0!4m2!3m1!1s0x48432e1d7e877cd7:0x1b15db652c0825bd!6m1!1e1

Now somewhat altered, it is nevertheless still distinctly recognisable as the building in our photograph. The shingled gable with the arched side door still remains (although the two windows in the side elevation have since disappeared). The rhythm of the windows on the ground floor of the entrance front is also the same, although the position of the entrance has been moved. Finally, the arrangement of the windows in the first floor can also be recognised from our original picture, although, as Dr St Leger points out, the woman in the window has since vanished!

Not wishing to base the attribution entirely on the formal appearance of the building, Dr St Leger has also provided us with additional corroborating historical evidence from the website www.myclonmel.com.

This is a very useful and comprehensive website and, under a section marked shops it lists No. 1 Parnell Street as being occupied in 1901 by a Davis & Co. Grocers.

We have our building!

Many thanks to Dr St Leger for taking the time to carry out such thorough detective work.

Eve McAulay,

3 April 2014.